Moth Report #7

The Privet Hawk, the Small Purple-barred, Argyresthia brockeella and Bisigna procerella

Welcome to my new subscribers (indeed, to all my subscribers!). This introductory blurb (in italics) at the beginning will remain much the same from post to post; please skip it if you’ve read previous posts!

This newsletter will remain free; I’ve no intention of converting it to a paid subscription. It’s aimed at readers who have a general interest in nature and natural history, but maybe don’t know much about moths. It’s not really aimed at people who regularly run their own moth traps, but of course they’re welcome to read it (even to criticise it if they wish!).

I run a light trap in my garden in Eastbourne (Sussex, UK) and the main objective of this newsletter is to post photos of some of the moths (and occasionally, other insects) that are attracted to the light. On average I run the trap about one night in three, and the plan is to write a post after each trapping night. In the morning I photograph any catches of special interest, then all moths and other insects caught in the trap are released (if they haven’t escaped already!).

This is my ninth year of running a garden moth trap, firstly three years in Eastbourne (2017-2019), then three in Hurstpierpoint (2020-2022), and then back in Eastbourne (2023 onwards). Hopefully, yet more house moves are off the cards for the foreseeable future!

Report for 1st July

When I put the trap out last night, conditions were looking almost ideal for a good night’s catch. The forecast humidity was down a notch compared with some previous nights, and a bit more cloud would have improved things a bit, but nonetheless I went to bed looking forward to a busy morning.

The warm and sunny day on Tuesday should also help, as most moth-ers are of the opinion that this encourages the emergence (from their pupae) of the adult moths. However, the lack of rain in past few weeks does mean the soil is quite hard; this is not good news for those moths which pupate in the soil, because sometimes it means that after they’ve emerged from their pupa (the proper word is ‘eclosed’) they then find the soil is too hard for them to be able to work their way up to surface before expanding their wings.

Anyway, when I went to check the trap in the morning, it was as full as I’ve ever seen it, and there were lots of moths on the walls and windows nearby. Once I’d finished checking everything I could, I’d got to 492 moths of 96 species! The total number of species is a record for me; the nearest I’ve got before is 92 species, in 2018, actually on the same date! The count of individuals is also a record for me; the same 2018 July night produced 427. So 500 moths of 100 species remains a rather elusive target for me. I suppose I could have got to the 500 if I’d spent more time hunting around in the grass and on the walls by the trap, but I doubt whether I’d have got to the 100 species.

Having said that, I just saw a Facebook post from a fellow moth-er who lives in the suburbs of Peterborough; not an environment which immediately suggests massive catches. But he is reporting c. 170 species! However, the post says he stayed up all night with his trap, checking them off as they flew in (such devotion to duty is beyond me!). This must increase the count quite a bit, because when I look at the trap before I go to bed, there are always moths there that have disappeared by the morning.

As far as the individual species go, there were several that I’ve only seen once or twice before, and four species that were completely new to me. I’ve selected a few of those to talk about in this post, but I’m starting with the biggest moth in the trap.

The Privet Hawk Moth, Sphinx ligustri

This moth is our largest resident hawk moth; although some other hawk moths (eg the Death’s Head) are larger, they are occasional migrants and are not resident here. Actually, there would be quite a lot to say about the Death’s Head, but I’m restricting this newsletter to moths I get in my garden trap, and I’m really not expecting ever to get a Death’s Head that way – the best I can do is direct you to The Wild Episode podcast about it.

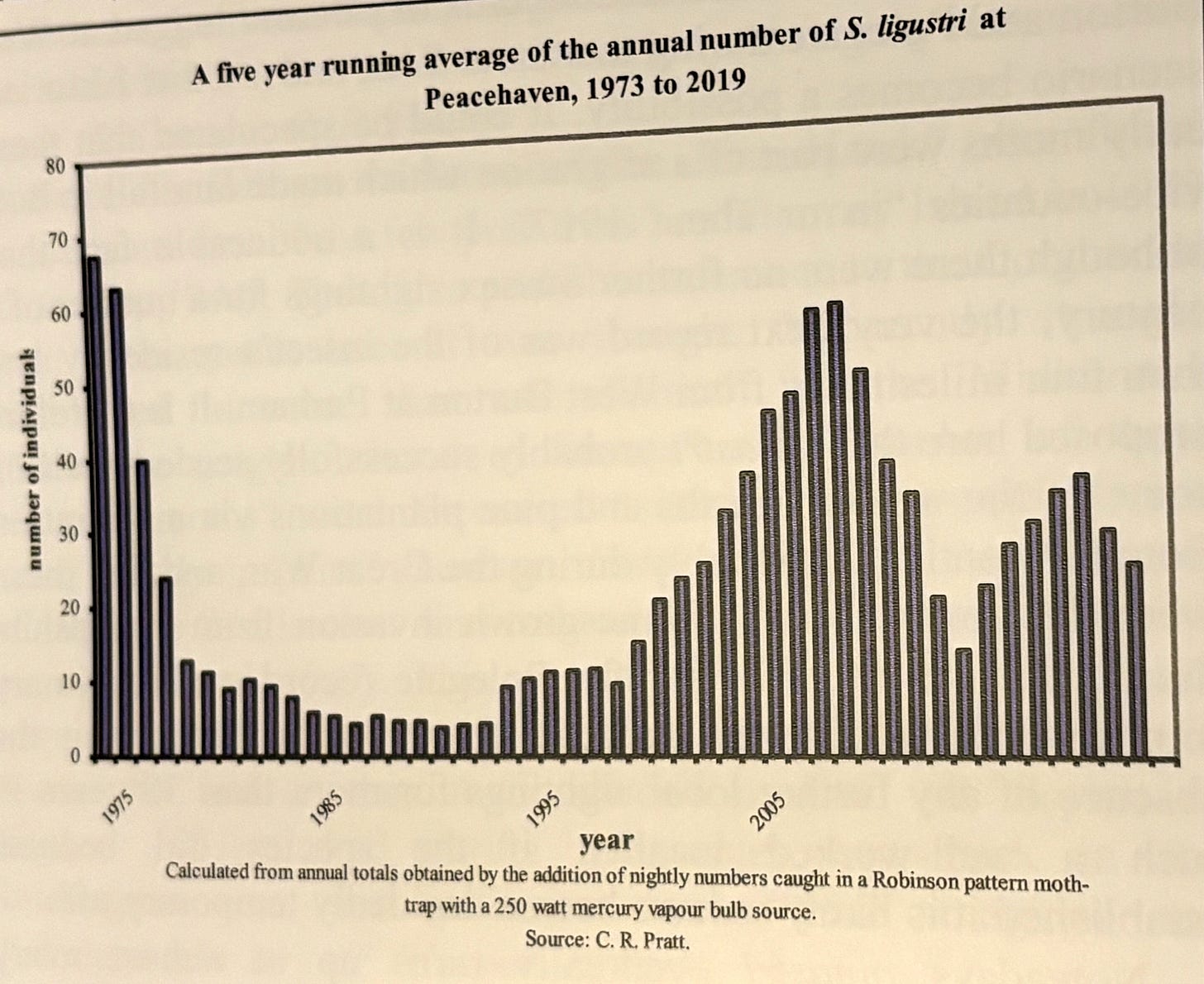

So, back to the Privet Hawk. When I was a kid in the 1950s many houses had privet hedges in their front gardens, and it was quite common to find the caterpillars of this moth feeding in the hedges. Sadly, not any more! After about 1975 there was a drastic decline in numbers throughout Sussex, and it disappeared completely from large parts of the East Sussex. This graph (taken from Volume 4 of A Revised History of the Butterflies and Moths of Sussex, by C.R. Pratt) shows the numbers caught each year in a light trap in Colin Pratt’s garden in Peacehaven, East Sussex.

As you can see, numbers recovered somewhat from about 2000 onwards. The last three years in this graph (2017 to 2019) show an average of about 30 moths per year. During the same years (in Eastbourne) I had an average of about 10 a year, so not as many as Colin in Peacehaven, but he uses a more powerful light source than I do, and also runs his trap more frequently. More recently my numbers have increased somewhat; last year I had 33 and this year I’ve had 17 already, including 4 last night (and there are usually more around in July than in June).

On the continent the Privet Hawk has always been a bivoltine species (i.e. two broods per year), but during the 20th century at least, in the UK it was always a univoltine species (one brood per year). However, in recent years adult individuals have been recorded later in the year than previously, so there is a possibility that it is becoming bivoltine here.

The Small Purple-barred, Phytometra viridaria

Of the four species new to me, only one belonged to the moth subgroup we call ‘macros’; the other three were in the ‘micro’ group. This is a distinction which is largely based on size, but there are some exceptions; the biggest micro is way larger than the smallest macro (something that often confuses beginners, because there separate ID guides for the two subgroups and it’s easy to look in the wrong one).

This is a moth that I’ve been wanting to see for a long time, as it usually has a striking purple bar across the wings. So where is it, you might well ask! If you Google this species, or check the relevant page on the Sussex Moth Group website you will see plenty of examples. However, there is a named colour form of this moth in which the purple bar is replaced with a brown one (called var. fusca), and it seems that that is what this is. So, just my luck!

The distribution map for this moth on the aforementioned website shows that although it is not a very rare moth, its found mainly on the South Downs in Sussex. Where I am in Eastbourne is therefore right on the very edge of its range.

Argyresthia brockeella

This is one of the micros that was new to me, and this really is a small one, with a total length of 6 or 7 mm. It’s also quite colourful, more so in the flesh than in this photo, having a gold and silver appearance. Many of the micro moths do not have well-known English or common names, although there as been a move recently to invent English names for all species. The name chosen for this moth reflects the same theme … the Gold-ribbon Argent.

This moth belongs to a family (the Argyresthidae) in which most of the species live and feed inside leaves or other parts of plants, rather than living on the outside and risking being picked off by a foraging bluetit. This species is no exception, feeding on catkins of the Silver Birch and the Alder.

If you think it’s sitting rather awkwardly, this bum-in-the-air pose is typical of the Argyresthidae.

Bisigna procerella

This is another colourful little micro. It’s not actually new for me, but I’ve only seen it once before, in 2018 (but not on the bumper night I had that year, that would have been a coincidence!).

This is a common moth in continental Europe, but the first UK record for it is not until 1976, when it was recorded in Hamstreet in Kent. Some time later it crept over the border into Sussex (the first record being in 2010), and it seems to have established a few colonies in NE Sussex. My two Eastbourne records do seem to be something of an outlier though, and although it seems to be slowly spreading, it remains a nationally scarce moth, largely confined to Kent and East Sussex.

So, July is off to a record start, will it last through the month I wonder. If you’ve enjoyed reading this report please give it a like, and/or make a comment, as I understand that that increases the chance that Substack will help promote the post. And the more subscribers/followers I have the more encouragement it will give me to continue the newsletter. Thanks for reading.