Welcome to my new subscribers (indeed, to all my subscribers!). This introductory blurb (in italics) at the beginning will remain much the same from post to post; please skip it if you’ve read previous posts.

This newsletter will remain free, I’ve no intention of converting it to a paid subscription. It’s aimed at readers who have a general interest in nature and natural history, but maybe don’t know very much about moths. It’s not really aimed at people who regularly run their own moth traps, but of course they’re welcome to read it (even to criticise it if they wish!).

I run a light trap in my garden in Eastbourne (Sussex, UK) and the main objective of this newsletter is to post photos of some of the moths (and occasionally, other insects) that are attracted to the light, and to say a little about them. On average I run the trap about one night in three, and the plan is to write a post after each trapping night. In the morning I photograph any catches of special interest, then all moths and other insects caught in the trap are released (if they haven’t escaped already!).

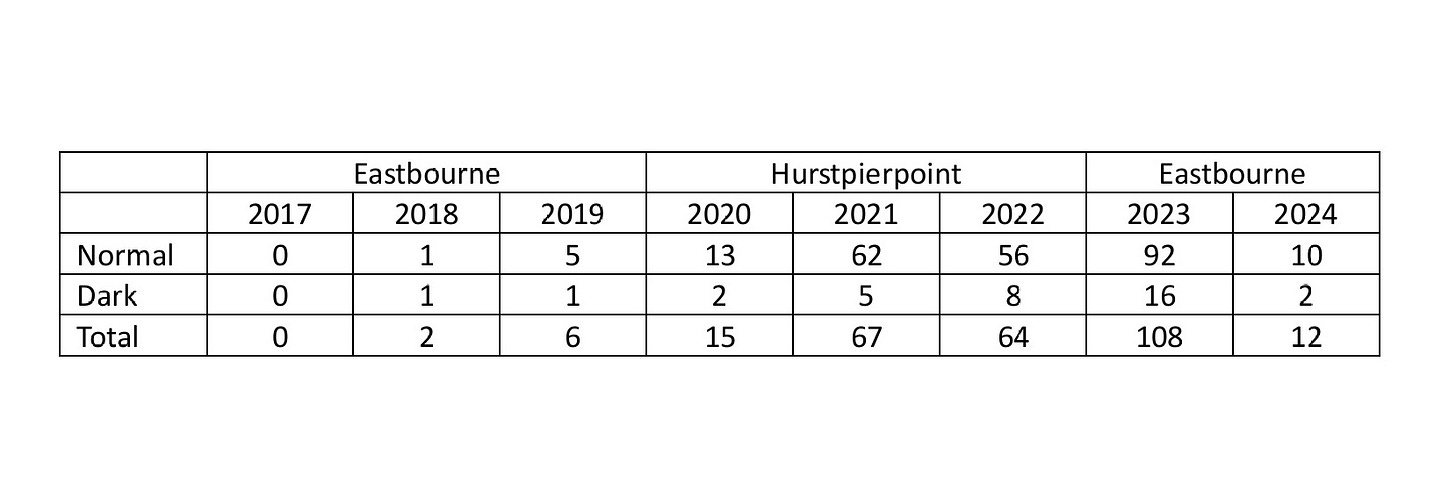

This is my ninth year of running a garden moth trap, firstly three years in Eastbourne (2017-2019), then three in Hurstpierpoint (2020-2022), and then back in Eastbourne (2023 onwards). Hopefully, yet more house moves are off the cards for the foreseeable future!

Report for 4th July

The weather forecast for the Friday night was somewhat less encouraging than on the previous night I ran the trap (1st July), a couple of degrees cooler, a noticeable breeze blowing and a brighter moon. So it wasn’t unexpected when I checked the trap before retiring for the night that there weren’t nearly so many moths about as there were on the trap’s previous outing; I spotted about 10 species, with only one I haven’t already seen this year.

The breeze seems to have kept up all night, and the morning, as I expected, it looked like a normal July catch; 143 moths of 44 species. Only three of these were first sightings for the current year, although one of them was a moth I’ve never seen before, which I’ll start this report with.

Eudemis porphyrana

This is a small moth, about 10mm long, which is described in the guide book as ‘very local’. That means it is only found in a few restricted localities, which might explain why I haven’t seen it before; if I’m not actually near one of those localities, it’s only the occasional one that goes wandering that I might get in my garden.

Looking at the map on the Sussex Moth Group website, it’s been recorded at only 15 1km squares from Sussex, and there aren’t any records from Eastbourne. The County Moth Recorder informs me that the nearest record to Eastbourne is Herstmonceux, and after that, Brighton.

The larvae are believed to feed on crab apple trees, and we have one in the garden, so maybe it’s put down a foothold here.

The Box Tree Moth, Cydalima perspectalis

Well, any gardener will have heard of this moth, although they might not know what the adults look like - it’s the caterpillars they will have encountered, ravaging their prized box hedges. The adult has two colour forms, the ‘normal’ form with the white triangle in the middle, and the less common dark form, missing this white patch. There were just two in the trap last night (one of each form).

This is an invasive species from Asia, first recorded in the UK (in Kent) in 2007. Since then it has spread rapidly, and is now a common moth in many parts of Britain. My own records demonstrate its growth in abundance in Sussex, well except for 2024, when there was a sudden drop in numbers.

I haven’t added 2025 because the maximum numbers for this species usually occur in September and October, we’ll have to wait and see what happens then!

Finally for this report, I’ve selected one of the most striking moths in the trap, the Buff Arches, which appeared for the first time this year. It’s never a common moth in my trap, the most I’ve ever had in one year is 4 (which was last year), although it is widespread in Sussex.

The Buff Arches, Habrosyne pyritoides

The Latin name for this species is quite poetic. The generic name Habrosyne is derived from the Greek habros, meaning graceful or elegant, and the specific name pyritoides translates from Latin as ‘like fool’s gold’, i.e. like iron pyrites. This is presumably because the wings have a metallic sheen, which is not really apparent in most photos, but is very stiking in real life if the moth is a fresh specimen.

This moth was given the specific name derasa by Linnaeus in 1767, which means ‘abraded’ or ‘shaved’, although it’s not clear what feature of the moth made Linnaeus give it that name, and the moth was known as that for more than 75 years. It was not until 1844 that it was discovered that the moth had been named pyritoides in 1766, by the German theologian and entomologist Johann Hufnagel, publishing his work in a rather obscure journal, the Berlinisches Magazin. So, following the law of temporal precedence, the moth is now known for its resemblance to iron pyrites!