Moth Report #20

The Chinese Character, the Mouse Moth and Carcina quercana (with a side helping of Fritz and Henry)

Welcome to my new subscribers (indeed, to all my subscribers!). This introductory blurb (in italics) will remain much the same from post to post; please skip it if you’ve read previous posts

This newsletter will remain free, I’ve no intention of converting it to a paid subscription. It’s aimed at readers who have a general interest in nature and natural history, but maybe don’t know very much about moths. It’s not really aimed at people who regularly run their own moth traps, but of course they’re welcome to read it (even to criticise it if they wish!).

I run a light trap in my garden in Eastbourne (Sussex, UK) and the main objective of this newsletter is to post photos of some of the moths (and occasionally, other insects) that are attracted to the light, and to say a little about them. On average I run the trap about one night in three, and the plan is to write a post after each trapping night, featuring two or three of the moths seen in the trap within the previous couple of weeks.

In the morning I photograph any catches of special interest, then all moths and other insects caught in the trap are released (if they haven’t escaped already!).

This is my ninth year of running a garden light trap, firstly three years in Eastbourne (2017-2019), then three in Hurstpierpoint (2020-2022), and then back in Eastbourne (2023 onwards). Hopefully, yet more house moves are off the cards for the foreseeable future!

Report for 17th August

The temperature overnight was still on the warm side, with not much moon. In spite of it being a bit more breezy than I’d like, the numbers were quite respectable with 165 moths of 39 species. There was a definite autumnal feel about the catch, including the first Delicate of the year; a moth which usually doesn’t put in an appearance until late September or even October. I’ll write a bit more about that in the next newsletter. Meanwhile, I’ve selected three moths for this newsletter, all of which have made their first appearance for this year in the past couple of weeks.

The Chinese Character, Cilix glaucata

Year total to date: 1 (11th August)

This is a small moth, although officially classed as a macro; it’s about 11mm long. And it looks quite unlike any of the other moths I’ve discussed in this newsletter so far. If you’re wondering where the head is, it’s hidden under the wings at the right-hand end (you can just see one of the legs sticking out). If evolution had a plan, which of course it doesn’t, the plan would be to make this insect look nothing like a moth, but to look like a dollop of bird poo instead; this moth is a bird-dropping mimic (well that’s what we call it in polite society (like Substack) - in practice we usually use a somewhat more colourful word!).

In fact, lots of moths are bird-dropping mimics - there’s even a whole book dedicated to them (it’s currently unavailable; if you’d like to buy my copy, it’s price on application!). The Chinese Character is not in my view one of the best ones; I’ll most likely cover another in some future edition. Actually, looking like an inanimate object such as a bird-dropping is not strictly what entomologists refer to as mimicry; historically that’s when one insect evolves to look like another. The more technical biological term for looking like something inanimate is ‘homotypism’.

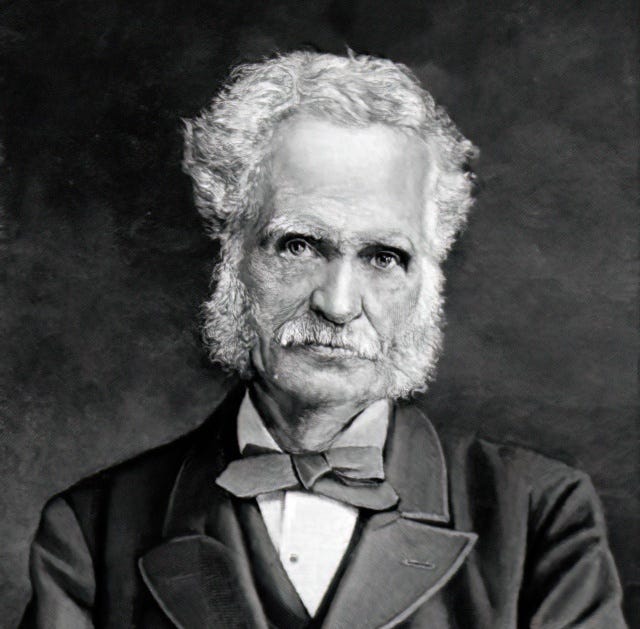

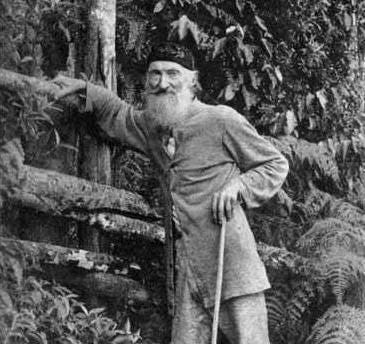

While we’ve strayed into the area of mimicry, though, I’d like to go off on a bit of tangent for a while and talk about a couple of people I’ve been reading about. I’m preparing a talk on mimicry, and was struck by some similarities between the two 19th Century naturalists whose names have become inextricably linked with this phenomenon: the Englishman Henry Bates (1825-1892), who first described what we now call Batesian mimicry, when a harmless species mimics a harmful or distasteful one, and the German Fritz Müller (1822-1897), who extended Bates’s work to the situation where two or more harmful species evolve to resemble one another, now called Müllerian mimicry.

It’s perhaps not surprising that both types of mimicry were first described in butterflies, because there are many examples of it in that group. But it’s interesting that both men did the work they based their papers on in Brazil; Bates spent 11 years (1848-1859) in the Amazon basin collecting and observing (mostly but not entirely insects), while Müller emigrated to southern Brazil in 1852, took Brazilian nationality and never returned to Europe. I don’t think they ever met though.

Both men were renowned for their skills as naturalists and as observers of the natural world. Müller’s work was not well known in the English-speaking world (although he corresponded with Darwin in faultless English, and Darwin called him ‘the prince of observers’). He wrote many papers on a wide range of animals, insects and plants, but because they were in widely scattered and sometimes obscure journals, and in different languages (mostly German and Portuguese), nobody at the time was aware of the extraordinary span of his biological expertise.

Müller’s father was a Protestant pastor, who can’t have been best pleased when his son became a committed atheist and joined a movement called the Lichtfreunde (Friends of Light) that emphasized reason over dogma, advocated for a more personal approach to faith and opposed the authoritarian behaviour of the established church. The movement also apparently sanctioned free love, although whether Fritz supported this aspect of the movement is not recorded. However, some four years before emigrating he was living ‘in sin’ with a local labourer’s daughter, Carolina, who had no formal education. They had a daughter, Louisa, in 1849, and then a second daughter, Anna, early in 1852. Shortly before emigrating Fritz and Carolina got married, Fritz having been persuaded by his sister that this would make things easier for Carolina in Brazil (it doubtless would have made them easier if they’d stayed in Germany too!). Sadly Louisa died shortly after Anna was born, but Anna survived the voyage to Brazil (ten out of twelve of the other children of nursing age on the voyage did not). Fritz and Carolina had ten children in total (nine of them daughters; their only son died in infancy).

And here’s the third and rather unexpected similarity between the two naturalists. After Bates returned from Brazil, he became friends with Sarah, the daughter of a butcher who ran a stall in the local market; like Carolina, Sarah had no formal education. They had a daughter, Alice1, in 1862 but did not get married until Alice was almost a year old. Henry and Sarah had five children in total. After the rather unorthodox (for the time) beginnings to their married lives, both Müller and Bates remained married to their respective spouses for the rest of their lives.

There’s a whole lot more I could write about these two men and their lives and works, but that’s quite enough dalliance for the moment and I should get back to the Chinese Character moth. Right in the centre of the forewing you can see a few white marks. In many specimens these marks are bolder and partially joined by white lines. It’s doubtful whether any of the entomologists who gave this moth its common name could read Chinese script, but it obviously looked to them like a bit of Chinese writing! The closest Chinese character to the mark would appear to be 山 (shan, meaning “mountain”).

For the scientific name, the meaning of Cilix is a bit obscure (although there is a character in Greek mythology with this name). The species name glaucata simply means “having a glaucous (silvery-grey) appearance”, which accurately describes the moth.

The Mouse Moth, Amphipyra tragopogonis

Year total to date: 1 (13th August)

From my early days of running a moth trap, while I was still a student, I remember the Mouse Moth as being relatively common, although unfortunately I no longer have any records from back then so I can’t confirm it. But it’s certainly not a common moth today (in spite of what it says in the book); since I re-started trapping in 2017 this is only the fourth one I’ve seen, and the first since 2020.

As you can see from the picture, it’s not a moth with any great claim to having a stunning visual impact; it’s just a grey moth with three small blackish spots on each forewing. But it’s not its appearance that gives it its name, it’s its behaviour. When disturbed, most moths adopt one of two tactics. One is to immediately fly off, and the other is to let go of what it was sitting on and drop to the ground, where as often as not it is hidden among the undergrowth. But the Mouse Moth does something different, in which it is quite unusual among moths; it scuttles away on foot, like a startled mouse! It’s quite surprising how fast it can move.

As far as the scientific name goes, the genus is relatively straightforward, meaning ‘about the fire’, which could be applied to lots of moths! The species name, tragopogonis, also has a straighforward meaning but it’s not clear why it was given to this moth. Tragopogon is a genus of flowering plants which includes Salsify and Goat’s-beard (aka Jack-go-to-bed-at-noon), and which literally translates as goat-beard. However, the caterpillars of the Mouse Moth feed on a large variety of herbacious plants, both wild and cultivated, so why this one genus has been specifically picked out is a bit of a puzzle.

Carcina quercana

Year total to date: 1 (13th August)

I’ve seen a handful of this colourful micro-moth every year since 2017 except for last year, so I was pleased to see it again a few nights ago; it’s getting near the end of its flight season so I thought I’d probably missed it for another year.

This moth has something of a claim to fame, because it is the only UK representative of the family it is placed in, the Peleopodinae. There are about 200 species in this family worldwide, mostly found in tropical and sub-tropical Asia. One of the features that separates these moths from other families is the length of the antennae, although there are one or two other families which have species with even longer antennae, sometimes two or three times the length of the wings.

The name Peleopodinae translates as ‘dark-footed’, although that would appear not to apply to the family’s UK representative. The genus name Carcina means restrained or confined (compare with a word like ‘incarcerate’). This possibly refers to the habit the caterpillars have of spinning a silken sheet to hide behind on the underside of a leaf, usually of oak (as the species name quercana indicates), or sometimes birch or other deciduous trees.

Well, that’s it for this edition. Now that I’ve decided to drop the word ‘trap’ from the title of this newsletter, there’s less point in linking the release of each edition to a specific trapping night. Instead, I’m planning to switch to a weekly release, probably on Tuesday mornings. Each edition will contain a summary of the catch(es) from the previous week, plus features about two or three moths which I’ve seen in the past couple of weeks. So the next issue will most likely be published on Tuesday next week, 26th August.

Also, if you’re a regular reader of this newsletter and know of other people who might enjoy reading it, please share it with them using the button below. The more regular readers I have, the more it will encourage me to continue writing it.

Alice might not have been Henry’s first child. There is circumstantial evidence that he fathered at least one child, a daughter, while he was in Brazil.

I’ve shared it with a moth trapper I know (who’s on FB groups but not Substack - yet). He doesn’t do as much as you, but I think would be interested.

Interesting read. I caught a Delicate last night in West Suffolk. Butterflies have been early this year so no surprises that moths are too.