Welcome to my new subscribers (indeed, to all my subscribers!). This introductory blurb (in italics) will remain much the same from post to post; please skip it if you’ve read previous posts.

This newsletter will remain free, I’ve no intention of converting it to a paid subscription. It’s aimed at readers who have a general interest in nature and natural history, but maybe don’t know very much about moths. It’s not really aimed at people who regularly run their own moth traps, but of course they’re welcome to read it (even to criticise it if they wish!).

I run a light trap in my garden in Eastbourne (Sussex, UK) and the main objective of this newsletter is to post photos of some of the moths (and occasionally, other insects) that are attracted to the light, and to say a little about them. On average I run the trap about one night in three, and the plan is to write a post after each trapping night. In the morning I photograph any catches of special interest, then all moths and other insects caught in the trap are released (if they haven’t escaped already!).

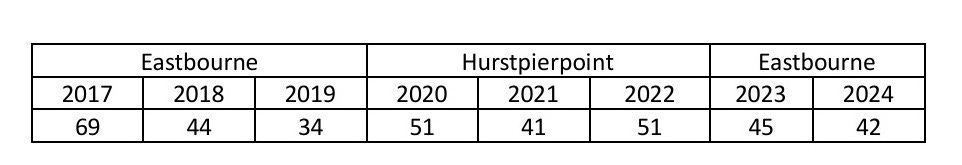

This is my ninth year of running a garden moth trap, firstly three years in Eastbourne (2017-2019), then three in Hurstpierpoint (2020-2022), and then back in Eastbourne (2023 onwards). Hopefully, yet more house moves are off the cards for the foreseeable future!

Now for a brief housekeeping note: starting from this issue, I’ve decided to change my (self-imposed) rules a bit. Previously I’ve only selected moths to feature in an edition that were actually present in the trap on the date the post is about. But I’ve decided that’s a bit restrictive and I will now allow myself to feature moths which I’ve had in the trap in the past two or three trapping sessions, although I won’t normally go much further back than that.

Report for 25th July

The forecast temperature for the night was still quite mild, also very little wind in the forecast and no moon, so things looked promising. On my last visit to the trap before going to bed (at about 23:20) I could see that the Jersey Tigers were back, after mysteriously being missing on the trap’s last outing; I could see at least five. And also a single Elephant Hawk moth arrived while I was checking.

When I checked the trap in the morning, the number of Jersey Tigers had not increased, but the number of Elephant Hawk moths had increased to four. In total there were 89 moths of 34 species, so quite similar to the previous trapping session (68 of 37). Only one species present was new for the year, but that was one which I was very pleased to see…

The Garden Tiger, Arctia caja

Year total to date: 1 (25th July)

When I was growing up, back in the 1950s, this was quite a common moth. Its hairy black caterpillar, known as a woolly bear, could often be seen on the ground searching for somewhere suitable to pupate. But these days it’s quite a rare moth, and it is now listed as a ‘Priority Species’ under the UK Biodiversity Framework. I didn’t see this moth at all last year, just three times the year before, and none for the three years prior to that (when I lived in Hurstpierpoint).

I’m sorry the photo of today’s moth is a bit blurred, but it’s the only one I managed to get which shows the brightly coloured hindwings, which serve as a warning to potential predators that the moth is toxic. When the moth is sitting at rest, the hindwings are hidden; when the moth is disturbed it flashes its hindwings, but it also tries to crawl or fly off (which is why my photo is blurred!). Resting photos are much easier:

Although minor variation in patterning is common (indeed no two are exactly the same), distinct aberrations are rare and there is only one main colour form (unlike for the Jersey Tiger, with its red and yellow forms). The county moth recorder for Sussex, Colin Pratt, has run a moth trap in his garden in Peacehaven since 1969. From then up to 2019 he recorded a total of 6,854 Garden Tigers (mostly in the early years!), but only two were what could justifiably be referred to as aberrations. Nonetheless, the colour and pattern on this moth is susceptible to environmental factors, and by manipulating temperatures during development quite a wide range of changes to the appearance of the adult moth can be induced. Some of the different colour forms that have been achieved with this moth can be seen here.

There are several moths in the UK which are grouped together by the common name ‘Tiger’. But why this is so in not so clear; only one (the Jersey Tiger) has a striped pattern. In other European countries the common names tend to reference flags or bears. The generic name Arctia is derived from the ancient Greek for bear (arktos), but whether this is why we call the caterpillars ‘woolly bears’ is again not clear. The specific name, caja (conferred by Linnaeus), is a bit of a conundrum. One possibility is that, in common with some of the other moths in this group, he wanted to give it a name with Roman connections. I’ve read that caja is the female form of the Roman name Caius (or Gaius), but if that was Linnaeus’s intention then he slipped up, because the usual female form for this name would be Caia (or Gaia), not Caja.

The Fern, Horisme tersata

Year total to date: 1 (22nd July)

In some ways, this moth is the lepidopteral equivalent of the bird-watcher’s LBJ; brown and undistinguished! Even so, the markings can be quite delicate. It’s a moth which I don’t see every year, and when I do, it’s only one or two (just 10 to date in nearly 9 years’ trapping).

In fact, it might not even be as many as that … and thereby hangs quite a tale! It all started back in May 2019, when I had one of these in the trap. As I sometimes did in those days, and still do occasionally, I posted a photograph of it on a Facbook group about UK moths. Shortly afterwards a comment appeared from a Belgian member of the group, saying that on the continent there was also a very similar species, H. radicaria, photos of which could sometimes be differentiated from H. tersata on the basis of some subtle differences in the markings. And this one looked to him more like radicaria than tersata, but that there were no confirmed UK records of radicaria (and no UK common name for it). Although my usual practice then was to release the moths as soon as I’d finished the photography, for some reason I’d not done this yet and I still had this one in a pot.

I contacted an expert, who got very excited and said please let him have the specimen. Well, to cut a long story short, he was able to confirm that it was indeed H. radicaria, the first time one had been recorded in the UK. To get it added to the UK list he had to write a paper for the Entomologist’s Record, and propose a common English name for it, for which he selected ‘Cryptic Fern’ (on the basis that it was hiding in plain sight).

So we now have two species of Horisme on the UK list. However, my specimen was soon after dethroned from the position of being the first UK specimen because another one, taken in Kent a couple of years earlier, also turned out to be radicaria, but nobody had spotted it!

I still record any Horisme that I get as Ferns, even though on the basis of their markings several of them look good candidates for being Cryptic Ferns.

By the way, if you’re struggling a bit with the Latin names, take pity on the Germans. Their common name for the Fern is ‘Graubrauner Waldrebenspanner’, which translates as Grey-brown Forest Vine Looper. The vine bit is a reference to the foodplant, Traveller’s Joy, aka Old-man’s Beard. But to be fair, that is at least a fairly accurate description of this moth, whereas ‘Fern’ is not and probably originates from some 18th century sort of romantic fantasy!

The Brimstone, Opisthograptis luteolata

Year total to date: 7 (most recent, 25th July)

Not to be confused with the Brimstone butterfly, the Brimstone moth is nonetheless the same lemony yellow colour, but rather smaller and with brown markings on the wings. Both are named after the element sulphur, for which brimstone is an old name, often found deposited around volcanic vents (hence the biblical ‘fire and brimstone’). The specific name, luteolata, is derived from the Latin luteus (meaning yellow), which is in turn related to lutum, the name of a plant which was used to produce a yellow dye. Very occasionally, specimens can be found in which the yellow ground colour is replaced with cream or even white, although I’ve never seen one like that.

This is a common moth throughout Sussex. It has two broods a year, and the second brood is usually the most abundant, flying in August and September; the one in the trap last night is probably an early emergence of the second generation. The county records show an increase in abundance since the turn of the century, while records from my own trap show its abundance to have been fairly stable over the past few years:

Well, that’s it for this edition. The next one will be in a few days’ time, depending on the weather!

Also, if you’re a regular reader of this newsletter and know of other people who might enjoy reading it, please share it with them using the button below. The more regular readers I have, the more it will encourage me to continue writing it.

These are beautiful! I have seen a garden tiger this year but I have never seen either of the other two. I love the brimstone in particular. What a beautiful moth. I have no moth trap but read recently about making “moth bait” with banana and brown sugar. Do you know whether that is effective for attracting them? I would love to see more moths- but the traps are expensive.