Moth Report #26

The Four-spotted Footman, Nomophila noctuella (aka Rush Veneer) and the Vestal

Welcome to my new subscribers (indeed, to all my subscribers!). This introductory blurb (in italics) will remain much the same from post to post; please skip it if you’ve read previous posts.

This newsletter will remain free, I’ve no intention of converting it to a paid subscription. It’s aimed at readers who have a general interest in nature and natural history, but maybe don’t know very much about moths. It’s not really aimed at people who regularly run their own moth traps, but of course they’re welcome to read it (even to criticise it if they wish!).

I run a light trap in my garden in Eastbourne (Sussex, UK) and the main objective of this newsletter is to post photos of some of the moths (and occasionally, other insects) that are attracted to the light, and to say a little about them. On average I run the trap about one night in three, and the plan is to write a post once a week, featuring two or three of the moths seen in the trap within the previous couple of weeks.

In the morning I photograph any catches of special interest, then all moths and other insects caught in the trap are released (if they haven’t escaped already!).

This is my ninth year of running a garden moth trap, firstly three years in Eastbourne (2017-2019), then three in Hurstpierpoint (2020-2022), and then back in Eastbourne (2023 onwards). Hopefully, yet more house moves are off the cards for the foreseeable future!

Report for w/b 22nd September

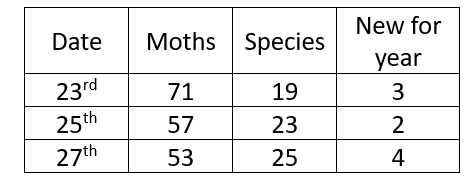

Relatively mild nights encouraged me to run the trap three times this week: Saturday night (27th) looked particularly promising because there was hardly any wind and the minimum forecast temperature was 14 degrees (Celsius), (compared with 11 for the other two nights). This is a summary of the results:

In terms of the number of moths, the Saturday night was a bit disappointing given the mild temperatures, but the species count was up a bit and 4 ‘new for year’ (NFY) species gave a welcome boost to my total year count, which now stands at 382 species. My previous highest count for January to September is 375, so I’m hopeful of beating my best annual total (398, from 2022).

The nine NFY species are all macros:

September Thorn (2)

Plumed Fan-foot

Frosted Orange

Large Wainscot (2)

Brindled Green

Feathered Brindle (2)

Black Rustic

Radford’s Flame Shoulder

Autumnal Rustic (2)

I’ll pick three of these to discuss in next week’s report; the September Thorn (definitely), the Frosted Orange (probably, it’s a cracker!) and one other. A couple of moths I’ve written about in previous reports were also present; a Red Underwing (bringing the year-to-date count to 3, higher than any previous year) and two Centre-barred Sallows (bringing the year count to 6).

I’m not planning to run the trap again until September is out, so we can take a brief look at the September statistics. In total there were 598 moths of 69 species. Both these numbers are down on the previous two years (2023 was 892 of 93 and 2024 was 639 of 80). However, with the exception of 2020 (another strong year) they are fairly typical for a September total. It maybe that because the seasons have been a bit ahead of themselves this year (the April and May results were both better than all previous years for which I have records), the numbers are falling off earlier than usual. If that’s the explanation, then October will also turn out to be below average. My species counts for previous Octobers have varied between 35 and 59, so we’ll wait and see what happens!

Anyway, let’s move on to look at some species seen recently. This week’s selection has a theme; all three are species regarded primarily as migrants in the UK.

The Four-spotted Footman, Lithosia quadra

Year total to date: 40 (latest 27th September (2))

This is the largest of a group of a dozen or so moths known as the footmen. The origin of this name is described by Tim Blackburn in his book The Jewel Box:

The origin of Footman for a group of species in the family Erebidae dates back at least to the eighteenth century, where it was first documented in The Aurelian, Moses Harris’s classic book on Lepidoptera1. The name was evidently inspired by the typical resting pose of these moths. Most Footmen sit with their greyish or yellowy wings tight to their bodies, looking like tiny stiff figures in formal tailcoat livery. Whoever coined their name had an artist’s eye, and a sense of humour.

In the Four-spotted Footman the females are larger than the males, and are the only sex to bear the four dots which give the species both its English common name and its scientific species name. Often only three of these dots are visible when the moth is at rest, with the fourth being hidden under the folded wings. In my picture above, the fourth dot is just visible.

The genus name, Lithosia, is from the Ancient Greek word lithos, meaning ‘stone’; this word gives rise to several other words in English, eg ‘monolith’. There are two possible explanations for why this name was chosen. One is that the absence of markings (in the male) gives the moth a plain appearance, like a plain stone surface. The other relates to the moth’s ‘foodplant’; I put it in inverted commas because it’s not really a plant at all, it’s lichen. Apparently, tree bark covered in lichen is assumed to also have a plain stone-like appearance, although to me it is anything but!

Most of the footmen moths have caterpillars that feed on lichen, although the reference books (at least those I’ve seen) are not usually specific about what kind of lichen; typically the furthest they go is to specify the substrate the lichens grow on, like ‘lichens growing on tree bark’, or ‘lichens growing on rocks and roof tiles’. However, I did find one which mentioned Dog Lichen (Peltigera canina) in connection with this species.

The UK population of this moth is a mixture of migrants from the continent and resident moths from colonies that have become established in the UK. Until recently, such colonies rarely managed to survive for more than a few years, and as a result the abundance of this species varied widely from year to year. As a migrant species, most records are from near the coast (the south coasts of England and Wales, and the East Anglian coast). Records from more inland locations are now becoming much commoner, as a result of more colonies becoming established.

The first year in which large numbers were recorded in Sussex is 1872. In the days before light trapping was possible most records were obtained using a technique known as ‘sugaring’ - a mixture of brown ale (or red wine), brown sugar and black treacle was smeared onto tree trunks and the smell attracted moths and quite a few other insects. Sometimes a dash of rum was added to the mix just before use as well, if it hadn’t already been consumed by the entomologist!

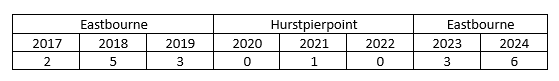

After 1872 this became a rare moth again, with short-lived colonies becoming established a few times right up until one night in August 2015, when 125 moths of this species were taken at a group of three light traps just along the coast from here (near Belle Tout lighthouse). Then the numbers were down again in 2016, but 2017 produced the highest numbers on record for Sussex (well over 400). But in 2019, fewer than 50 were reported for the whole county. These are my own counts from 2017 onwards:

The reduced numbers in Hurstpierpoint compared with Eastbourne are probably a reflection of the fact that it is further inland. But overall, it is clear that this is a moth I didn’t see a lot of … until this year, that is! Currently this year’s total stands at 40, double the total for the preceding 8 years. Most likely this indicates that a colony has become established in the near vicinity. It’s also possible that this is a mass migration event, since another migratory species (Nomophila noctuella, see below) has also been quite common this year.

Nomophila noctuella

Year total to date: 88 (latest 27th September (2))

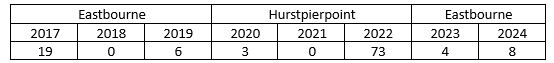

As mentioned above, this is another moth with a strong migratory habit, and as such its numbers also vary wildly from year to year. These are my annual catch totals:

And so far this year, the total is 88. It’s interesting that mass migration events don’t always work in the same way for different species, even if they are on the wing at the same time. So while numbers for this species and for the Four-spotted Footman are both abnormally high this year, in 2022 this species was numerous but the Footman was not.

Nomophila noctuella is technically a micro-moth, which is why I’ve given only its scientific name, but it does actually have a widely accepted English common name, the Rush Veneer. It’s one of the larger micros, with a wing length of about 13mm. It breeds regularly in the UK, and is distributed nationwide, including the Orkneys and Shetland, so its distribution map looks quite different from that of the Four-spotted Footman.

The genus name Nomophila is derived from the (ancient) Greek nomos, which can mean ‘pasture’ or ‘meadow’ and also ‘law’ or ‘order’. Most likely it is the first meaning which is relevant here, so together with the -phila ending it means ‘lover of meadows’. This is quite fitting as the moth can often be disturbed by day in the chalk downland meadow near where I live. Other English words derived from nomos usually take the other meaning, e.g. ‘nomocracy’ denotes government based on the rule of law. Note however that ‘nomophobia’ does not mean fear of the law; rather it’s a modern coinage that means fear of being stuck with no mobile phone/signal! The species name noctuella of course relates to its nocturnal character, although since the vast majority of moths are entirely nocturnal it does seem a bit odd to give this name to a species which can also be found flying in the daytime.

The intensity of the markings on the wings can vary from almost missing entirely to really quite pronounced. Just as Melissa Harrison would expect!

The Vestal, Rhodometra sacraria

Year total to date: 2 (both 19th September)

The Vestal looks like quite a delicate little moth, but appearances can be deceptive because this moth, like to two discussed above, is a migrant from the continent. In the UK it has been reported widely throughout England and Wales, with several reports from Scotland (including Shetland).

The ground colour varies between pale lemon yellow and a dull straw colour, and there is a diagonal stripe which is usually either brown or pink. Sometimes the ground colour can be suffused with pink, but I’ve never seen one like this (the one at the bottom right is just beginning to go that way). The colouring of the moth is dependent on the temperatures experienced by the pupa, with warmer temperatures leading to brighter colours.

Unlike the two species discussed above the Vestal has not been know to survive a UK winter, so all those seen here are either migrants or their first generation descendents. Like other migrants, its numbers can fluctuate from year to year (in 1947, 1983 and 2006 it was particularly numerous), but my annual totals for this moth have been zero four times, and when not zero they’ve never been more than four. Unlike the two species discussed above, the numbers I’ve seen this year (so far, at least) are not abnormally high.

The moth’s English name, the Vestal, naturally raises the question of what is the association between this moth and the Vestal Virgins of ancient Rome. To investigate that we can start with the species name given by Linnaeus, sacraria. In Latin, this is a plural; the singular is sacrarium. The word describes a sacred place; for example in Roman homes the sacrarium was a shrine to the household gods. In many Catholic churches, a sacrarium is a special sink used for the disposal of sacred substances; rather than draining into the sewer system it drains directly into the earth, so that consecrated substances are returned respectfully to nature without being contaminated by other, less beatific, waste material. But it’s not at all clear what Linnaeus intended by using the plural form, sacraria. It’s possible that he thought of it as the female form of the noun (although he wrote all his scientific works in Latin and clearly knew a lot more about it than I do). It’s perfectly possible that he was correct and it is my AI sources that are wrong!

In Peter Marren’s book on moth (and butterfly) names, he writes:

The moth named The Vestal is yellow with a red stripe, which Linnaeus seems to have believed was the costume worn by the Vestal Virgins (he may have confused it with the purple-striped togas worn by senators). He named the moth sacraria, the female keeper of the sacred temple.

That all sounds very plausible, but I’ve been unable to find online any reference to the female keeper(s) of the sacred temple being called ‘sacraria’. Looking after the sacred temple was in fact the job of the Vestal Virgins, who were priestesses of Vesta, the goddess of the hearth2. And their costume did include a plain white tunic (the Tunica alba) and woollen fillets or ribbons (the Infula) tied around the head, often in red and white - the colours associated with sacred rites.

So overall the picture is somewhat confused (and confusing). It seems fairly clear though that Linnaeus’s intention was to link the moth in some way to the Vestal Virgins. The French common name, La Sacrée (The Sacred One), keeps the religious flavour without pointing specifically to the Vestal Virgins.

That’s it for this week. The next issue is scheduled for Tuesday, 7th October.

The first edition was published in 1778. There was second edition in 1840, which can be viewed online (here). It does indeed give a brief description of one of the Footmen moths (now called the Red-necked Footman), although it doesn’t say anything about the origin of the name.

Now I know where Swan Vesta matches got their name, well at least the Vesta part of it!

Interesting. I wonder if the fact that more colonies of the four-spotted footman are surviving could be linked to better air conditions (following the Clean Air Act 1956, the move away from heavy industry and the fitting of catalytic converters to cars), which favour lichen growth?