Moth Report #25

The Large Yellow Underwing, the Centre-barred Sallow and the Horse Chestnut Leaf Miner

Welcome to my new subscribers (indeed, to all my subscribers!). This introductory blurb (in italics) will remain much the same from post to post; please skip it if you’ve read previous posts.

This newsletter will remain free, I’ve no intention of converting it to a paid subscription. It’s aimed at readers who have a general interest in nature and natural history, but maybe don’t know very much about moths. It’s not really aimed at people who regularly run their own moth traps, but of course they’re welcome to read it (even to criticise it if they wish!).

I run a light trap in my garden in Eastbourne (Sussex, UK) and the main objective of this newsletter is to post photos of some of the moths (and occasionally, other insects) that are attracted to the light, and to say a little about them. On average I run the trap about one night in three, and the plan is to write a post once a week, featuring two or three of the moths seen in the trap within the previous couple of weeks.

In the morning I photograph any catches of special interest, then all moths and other insects caught in the trap are released (if they haven’t escaped already!).

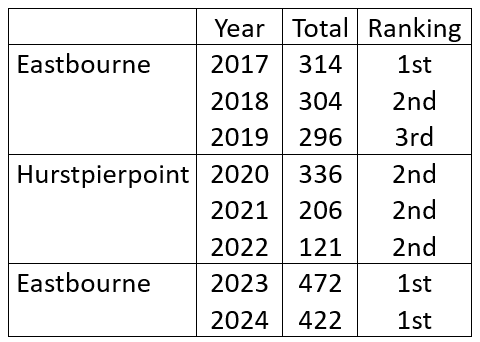

This is my ninth year of running a garden moth trap, firstly three years in Eastbourne (2017-2019), then three in Hurstpierpoint (2020-2022), and then back in Eastbourne (2023 onwards). Hopefully, yet more house moves are off the cards for the foreseeable future!

Report for w/b 15th September

I ran the trap twice during the week, on the 17th (Wednesday) and 19th (Friday). Weatherwise, the conditions on the two nights were quite similar, with temperatures in the high teens (Celsius), maybe a degree or two warmer on the Friday than on the Wednesday. Well, except for one thing … the wind. On the Wednesday it was quite breezy, with wind speeds of around 15 mph, whereas on Friday the speed was around 5 mph. This made quite a difference to the catch. On Wednesday it was 38 moths of 10 species, with nothing of note except for another Pearly Underwing (following my first ever on the 4th, see here for a discussion of that species). On the Friday, the numbers shot up to 148 moths of 33 species. This included quite a few (45) Large Yellow Underwings (see below for more about this species), and three species recorded for the first time this year (Red-green Carpet, Vestal and Lunar Underwing). Also of note were the catches for a couple of moths usually regarded as migrants from the continent, and which usually turn up (if at all) in ones and twos. One of these is the Four-spotted Footman, of which there were 7; my highest annual count for this species previously is 6! The other is Palpita vitrealis, of which there were also 7. The highest annual count for this species up to and including 2023 was also 6, but last year it was 20 (and this year is currently at 23). See here for more on this species. These could just be the result of high migrant activity, or it might indicate that these species are becoming resident locally.

While I’m not intending to do this regularly, I’ve listed the whole catch for the 19th in an addendum at the end of this report. This was prompted by Cat who gave a full list of her catch from 5th September on a Scottish Island.

Let’s move on to look at some species seen recently:

The Large Yellow Underwing, Noctua pronuba

Year total to date: 345 (latest, 19th Sept (45))

There are several UK moths which have yellow hindwings, collectively known as the Yellow Underwings. This one is the largest, with a wing length of about 25mm, and it is also (at least in my area) by far the commonest. Indeed it’s one of the commonest among all species, regularly coming in the top three most numerous species each year. Here are my annual totals for the past few years:

For the current year the total so far is 345, with the maximum for a single night being 45 (for 19th September), and there’s been at least one in the trap every time I’ve run it since the beginning of June. Across all years, the maximum for a single night is 71 (5th September 2024). Most years the first Large Yellow Underwing appears around the end of May or the beginning of June (this year was an exception, with the first seen on 1st May), then the numbers gradually build up until they reach a peak in September. In October the numbers are much reduced, and in some years just one or two stragglers manage to keep going into November.

You can see from the pictures above that the colour and the degree of patterning on the forewing is very variable. One feature which is always present though is the black mark near to the tip of the forewing; if this is missing then most likely it’s a different species. Usually the yellow hindwing is not visible when the moths settle; they are very reluctant to sit with the hindwing exposed. However among the catch from the 17th I was surprised to find a rather tatty one sitting in the trap with one of the hindwings showing:

When the moth flies off there is always a flash of yellow; and flying off is something this species is very good at. Most of the larger moths require a certain amount of time to warm up their flight muscles before they take off - they sit vibrating their wings in order to do this. But not this one - a slight touch is often all that is needed and they can fly off without any warm up exercise first.

The moth’s native range is Europe, but in 1979 one was found in Nova Scotia. Since then it has spread across much of Canada and the USA, where it is now one of the most widespread non-native moths. One of the reasons why it spread so quickly, and also perhaps one of the reasons it’s common is that the caterpillar is not a fussy eater; it will eat virtually any herbacious plant and several different grasses.

The caterpillar is sometimes called a cutworm, because of the way it feeds, which is similar to the Pearly Underwing I discussed last week (here). It remains hidden in the soil by day, and comes out to feed at night on the nearest bit of greenery it can find, often just cutting it off at the base of the stem. The caterpillars feed up during the autumn, and hibernate as larvae before pupating in the spring. Unlike the Pearly Underwing, known as the Variegated Cutworm in the US, this moth has largely retained ‘Large Yellow Underwing’ as its common name there.

The genus name for this species, Noctua, means ‘little owl’ in Latin. It’s actually the type genus for the entire (and large) family, the Noctuidae. As a result the family is sometimes called the ‘owlet’ family, but is not to be confused with the spectacular Asian moths known as Owl moths, which are in a different family altogether, for example Brahmaea wallichii. See here for a Flickr photo. The owl reference in the case of the Noctuidae is most likely due to the fact that nearly all the species in this family are nocturnal.

The species name, pronuba, was given to this species by Linnaeus in 1758. The literal translation is ‘for the bride’; in ancient Rome ‘pronuba’ was the title of the matron of honour, or bridal attendant, at a wedding. If you’re a regular reader of this Substack newsletter, you might be getting the impression that Linnaeus was a bit obsessed with brides and weddings; he also gave the Red Underwing moth a species name meaning ‘bride’, nupta (see here for my report on this moth). As with many of Linnaeus’s names it’s not entirely clear what the link is. However, it’s interesting to speculate whether the French have some inside knowledge in this case; their common name for this moth is ‘La Noctuelle fiancée’ - the betrothed Noctuid!

The Centre-barred Sallow, Atethmia centrago

Year total to date: 5 (latest 19th Septemeber (3))

There’s an informal1 group of moths from the same family as the Large Yellow Underwing discussed above, the Noctuidae, which are collectively known as ‘the Sallows’. They are all moths of the autumn, with colours to match; predominantly yellows and browns with the occasional flash of pink. None of them is common, at least not around Eastbourne! Most years I see three or four species from the group, mostly in ones and twos. There are only three species for which I’ve ever had a year count exceeding 10, and some of them I’ve never seen at all.

The Centre-barred Sallow is the one I see most often, and the only one which I’ve seen every year, the largest number I’ve seen in a year is 34 (in 2020), but more usually the year count is in single figures or in the low teens. It’s also the only one I’ve seen so far this year. Before 1970 this was a rare moth, but since then it has increased in numbers substantially. It is now found throughout most of England and Wales and southern Scotland, with a more patchy distribution in northern Scotland. However, the flight season is usually quite short, late August to late September, so it looks like I might not improve on this year’s count of 5, which only just exceeds my lowest annual total for this species of 4 (from 2017). The caterpillars feed on ash, which is having a tough time at the moment, so it perhaps would not be surprising if the numbers decreased.

The ‘classical’ colouration is shown in the top left photo, but variations on the colour form are seen relatively frequently.

This is the only UK species from the genus Atethmia, and this is a word with no obvious Latin or Greek connection. It’s possible that the A- at the start means ‘without’, but what it is lacking is not clear! The species name centrago is by comparison straightforward - most likely it comes from the Latin centrum (‘centre’) and ago, a verb root meaning (among other things) ‘to bear’. So this is likely a reference to the central bar that also features in the English common name. I couldn’t find any other references to the central bar in the moth’s other European names. The French name is ‘La Xanthie Topaze’. ‘Xanthie’ is a gallicised form of Xanthia which is the genus name of some closely related moths and is based on the Greek xanthos (‘yellow’). And ‘topaze’ also relates to the colour, of course.

The Horse Chestnut Leaf Miner, Cameraria ohridella

Year total to date: 4 (last sighting 13th September)

Firstly, apologies for the poor quality of this photo; this is a very small moth (about 3.5mm long) and also usually very active; I’d need to be a much better photographer to get a decent photo of one of these. Some people seem to manage it though, for example this photo posted on Flickr.

Although it’s a small moth, this is one which has come to many people’s attention in recent years … or at least its effect on horse chestnut trees has. This is because the larvae form what are known as ‘blotch mines’ on the leaves of the tree, as they feed between the upper and lower epidermal layers of the leaves. A tree sometimes has a large number of these mines, which can weaken the tree and cause early leaf fall. The trees usually recover, but being weakened makes them more susceptible to disease and environmental stress. Here’s a Flickr photo showing how the leaves look when they are infected.

This phenomenon was first noticed in 1984 in ornamental horse chestnut trees growing around Lake Ohrid in Macedonia, with large numbers of trees showing severe damage. At the time the moth did not have a scientific name; it was formally described in the following year, and given the name Cameraria ohridella - with the species name based on the geographical region where the outbreak occurred. There was some debate about where the moth had come from, or whether it had been in the Balkans all along. Looking back at herbarium specimens of horse chestnut leaves from the region, pressed leaves including ohridella leaf mines were noticed in samples from the Balkans and central Greece as far back as 1879, so it was concluded that the moth is most likely a native of that region. Something must have happened in the 1980s, perhaps a genetic mutation of some kind, that enabled the moth to suddenly increase in numbers and become invasive.

The genus in which this species was placed, Cameraria, was named in 1874 by the American entomologist Vactor Tousey Chambers (1830-1883), who specialised in micro-moths, especially leaf-miners. It now contains around 60 species. The name aptly describes the leaf-mining habit; it’s made from the Latin camera (‘room’ or ‘chamber’) with the suffix -aria (‘associated with’), describing the space inside the leaf where the larvae live.

Since its discovery the moth has spread rapidly throughout most of Europe, and the first UK record is from Wimbledon in 2002, since when it has spread throughout England and Wales, with a few sightings from Scotland, particularly around Edinburgh. The first record for Sussex was from 2003, near the southern boundary of Gatwick airport. Colin Pratt (in his book A Revised History of the Butterflies and Moths of Sussex, Vol. 1) takes up the story from there:

Colonising the county from west to east, ohridella then overran East Sussex at a rate of about five miles per annum - by 2004 it had reached Falmer, by 2005 to Lewes, by 2006 to Bewl Water, by 2008 to Bexhill, by 2009 to Icklesham, and by 2014 to the Kent border at Rye. The speed of colonisation is typical for a fast-moving lepidopteron but the subsequent density of settlements is almost unprecendented. So successful has this colonisation been that caterpillar mines are currently commonplace in the leaves of almost every white-flowered horse chestnut in the county.

Although the larvae are now very common large numbers of adults are rarely seen, although there are a few reports of the adults being seen in swarms around stands of horse chestnut trees. At light traps, however, it’s rare to see more than one or two at a time, and my own records reflect this. Some years I don’t see it at all, and my current year count of 4 is the highest since 2018 (when it was also 4).

Readers of my generation will remember the time when milk bottles had foil tops, and if the milkman left the tops uncovered on the doorstep, they were vulnerable to attack by blue tits which had learned to pierce the caps to get at the cream beneath. Well, it seems that blue tits (and great tits and marsh tits) are learning a new trick now - opening up the leaf mines of this moth in order to get at the nice juicy caterpillars inside. This predation pressure on the moth should help to control the damage being done to our horse chestnut trees.

That’s it for this week. The next issue is scheduled for Tuesday, 30th September (which will feature the three species indicated in the list in the addendum below).

Addendum: Full list for 19th September

(Links are given for species I’ve discussed in previous editions of the Moth Report)

Macro-moths:

Blair’s Mocha (2)

Vestal (2) (to be discussed in next week’s Moth Report)

Garden Carpet (3)

Red-green Carpet (1)

Double-striped Pug (5)

Cypress Pug (2)

Brimstone (1)

Dusky Thorn (7)

Willow Beauty (5)

Light Emerald (5)

Four-spotted Footman (7) (to be discussed in next week’s Moth Report)

Silver Y (1)

Copper Underwing agg (2)

Angle Shades (1)

Lunar Underwing (2)

Centre-barred Sallow (3) (see discussion above)

Heart and Dart (1)

Large Yellow Underwing (45) (see discussion above)

Broad-bordered Yellow Underwing (1)

Lesser Yellow Underwing (7)

Lesser Broad-bordered Yellow Underwing (1)

Square-spot Rustic (1)

Setaceous Hebrew Character (1)

Micro-moths:

Tachystola acroxantha (1)

Carcina quercana (1)

Blastobasis adustella (1)

Archips podana (1)

Epiphyas postvittana (1)

Dichrorampha acuminata (1)

Palpita vitrealis (7)

Nomophila noctuella (17) (to be discussed in next week’s Moth Report)

Cydalima perspectalis (4)

Agriphila geniculea (2)

By ‘informal’ I mean it’s not a group based on any scientific principles (like a family, or a genus). It’s just a group of moths with similar colouration and similar common names.

I would like to raise an objection. It is UNFAIR for some species to show such a degree of variation given that there are 2,500+ species of moth in the UK and loads of them ALREADY LOOK BASICALLY THE SAME.

I trust you will convey this objection to the relevant authorities. Thank you.

Thanks for the interesting read!