Welcome to my new subscribers (indeed, to all my subscribers!). This introductory blurb (in italics) will remain much the same from post to post; please skip it if you’ve read previous posts.

This newsletter will remain free, I’ve no intention of converting it to a paid subscription. It’s aimed at readers who have a general interest in nature and natural history, but maybe don’t know very much about moths. It’s not really aimed at people who regularly run their own moth traps, but of course they’re welcome to read it (even to criticise it if they wish!).

I run a light trap in my garden in Eastbourne (Sussex, UK) and the main objective of this newsletter is to post photos of some of the moths (and occasionally, other insects) that are attracted to the light, and to say a little about them. On average I run the trap about one night in three, and the plan is to write a post once a week, featuring two or three of the moths seen in the trap within the previous couple of weeks.

In the morning I photograph any catches of special interest, then all moths and other insects caught in the trap are released (if they haven’t escaped already!).

This is my ninth year of running a garden moth trap, firstly three years in Eastbourne (2017-2019), then three in Hurstpierpoint (2020-2022), and then back in Eastbourne (2023 onwards). Hopefully, yet more house moves are off the cards for the foreseeable future!

Report for w/b 17th November

The first part of the week featured some very cold nights, but the Tuesday night (18th) forecast was for a slightly less cold night (minimum 5 degrees Celsius) so I put the trap out on the off chance - but to no avail. Then the end of the week turned milder but with more wind and some rain. I picked the Sunday night (23rd) as having the best chance, and got just two moths - the seventh November moth for the year and a Sprawler, a new record for the year.

Do you get all your deliveries of the Moth Report?

I think most of my subscribers receive my Reports as an email, while a few have switched off this option and view the Reports in Substack. I’ve registered myself as a subscriber so that I can see how the emails look. But a couple of times recently my email has never arrived (and I checked the spam folder!). Also, the list of email addresses that Substack tells me it has sent emails to is only about 70% of the total number it tells me it has sent out. I understand that if emails bounce back Substack will drop the addresses from its list, but I’d be surprised if that accounts for the difference (and I use a dedicated address for mine so I know it was never full).

So if you don’t receive the Report on a Tuesday morning (without having been warned in the previous Report I was taking a week off), please go onto the Substack website to find the missing Report, and leave a comment to the effect that you didn’t get the emailed version. Thanks.

Anyway, let’s move on to look at some species seen recently.

The Feathered Thorn, Colotois pennaria

Year total to date: 3 (13th November (2))

The Feathered Thorn is a distinctively shaped moth with rather variable colouration; these four demonstrate some of this range; see the Sussex Moth Group website for a sightly more extreme range (here).

I mentioned that I had seen my first for this year on 6th November in my report for that week (here), and had a comment from one of my two most supportive subscribers, Melissa Harrison, that one of her friends plays in a group called ‘The Feathered Thorns’. What a great name for a band! It started me wondering what other moth species might provide a good band name. Obviously a group called ‘The Clouded Drabs’ wouldn’t get many gigs, no matter how good they were. And ‘The Turnips’ or ‘The Cabbages’ would only work for a comedy band. ‘The Flame Brocades’, perhaps? I quite like ‘The Tawny Pinions’ and ‘The Angle Shades’. Suggestions welcome in the comments!

The website for The Feathered Thorns is here. I see they’ve got a track called ‘Moths’, so the name clearly isn’t just an accidental coincidence. I’m not qualified to comment on how good they are, well except in the technical sense (which is fine); my musical tastes don’t extend beyond classical. My son, on the other hand, is a competent heavy-metal guitarist and he writes and records his own stuff. He listened to some of their songs, and agrees with me that they’re technically fine, but (also like me) he claims that they’re not his kind of music so he can’t really judge them from a creative point of view!

The ‘Feathered’ part of the moth’s name is said to be a description of the antennae of the male (see the top left photo), but only the males have this feathering, which they use to pick up the pheromones released by the females. The species part of the scientific name, pennaria, also relates to this feature, it comes from the Latin penna, meaning ‘feather’. The thorax of this moth is also unusually hairy. This probably helps reduce the reflection of a bat’s echo-locating clicks, and so might give the moths a survival advantage. I don’t know whether the band members in The Feathered Thorns grow their hair unusually long; if they do then that could be why they chose this particular moth as the name for their band!

This moth is not known to be migratory, but two specimens were recorded on the Royal Sovereign light vessel moored in the English Channel seven miles off Bexhill, one in 1952 and another in 1956. The first such vessel was stationed on the shoals off Bexhill in 1875. In 1971 it was replaced with a lighthouse built on a concrete platform over the shoals; this lighthouse was manned until it was automated in 1994. Then in 2022 it was decommisioned, and dismantled the following year. Just two moths in around 120 years of having a manned light in the Channel is not strong evidence for regular migration, although collecting wildlife data (birds and insects) was not one of the official duties of the keepers and it would depend on the interests of the individuals concerned whether they did this or not. I lived in Bexhill for about 25 years (left there in 2016), and can remember seeing the Royal Sovereign light from the promenade; if it’s visible from seven miles away it would have been a very powerful moth attractant! I missed the news about it being decomissioned.

I don’t usually include photographs of the caterpillars of the moths I feature, for the simple reason that I don’t actually have many of my own. But for this moth I do have one, so here it is:

This moth (along with several others I’ve featured) is a member of the family Geometridae, which translates as ‘earth measurer’. The reason for this name is that the caterpillars have legs only at the back (two pairs) and front (three pairs) ends, whilst most other families have extra pairs of legs along the length of the body. The manner of locomotion of the Geometrid caterpillars is to pull the hind legs right up to the front legs, and then move the front legs forward as far as they can reach, and draw the hid legs up again, etc. This causes the body to alternate between stretched straight and bent into a loop, and gives the appearance that the caterpillar is measuring the ground as it moves forwards. It also gives rise to an alternative name for the family, the ‘loopers’. The German common name for this species is ‘Federfühler-Herbstspanner’ … the ‘spanner’ at the end of the name translates as ‘looper’ or ‘measurer’, and Herbst is autumn, so the second half of the moth’s name means ‘autumn looper’. The first part translates as ‘feather-feeler’, where the ‘feeler’ part refers to the antennae. When I was young I remember people using the word ‘feelers’ as a child-friendly version of ‘antennae’.

The November Moth (agg), Epirrita sp.

Year total to date: 7 (latest: 23rd November)

Well here am I thinking of including an entry on the November moth in the next but one Moth Report, while reading the Saturday edition of The Times, and what should I see in the paper but a picture of a November moth! It’s in Nature Notebook:

All Epirrita dance an etherial jig in the headlights and hover ghostly outside the sitting-room window at night.

John Lewis-Stemple, The Times, Saturday 15th November.

There are four UK moths in the genus Epirrita; they are all variable and the markings on the different species overlap substantially, so it is never safe to try to identify them to species level just from the appearance of the wings. One of them, E. filigrammaria, the Small Autumnal Moth, has an earlier flight season than the others, so if seen before late September then it can be confidently identified as such. But (a) I’ve never recorded one as early as September, and (b) neither has anyone else in Sussex (according to the Sussex Moth Group website), so that one can definitely be ruled out!

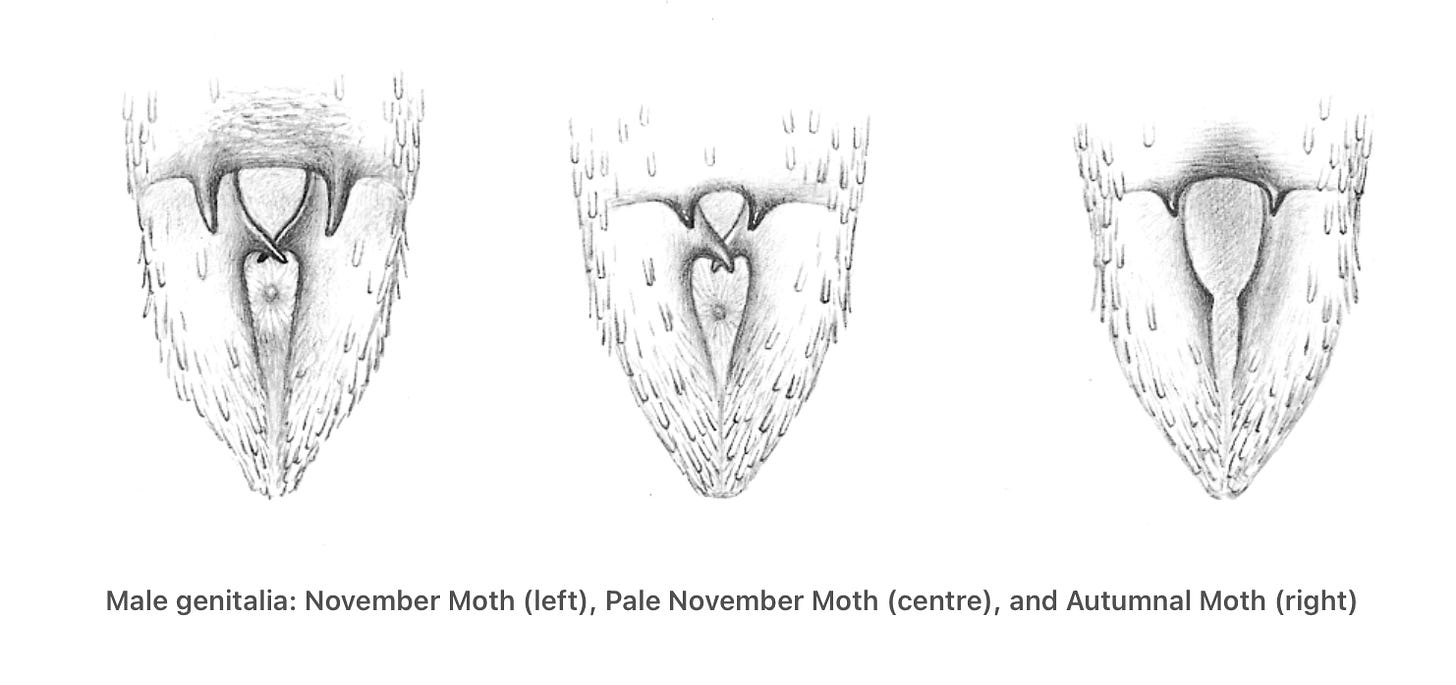

It’s supposed to be possible to separate the males of the other three species by looking at their genitalia with a hand lens or low-powered microscope without harming the moths (well apart from injuring their dignity). Here’s what they’re supposed to look like:

And here’s a photo I took of the relevant area:

Well, you tell me! But the commonest species is the November Moth, Epirrita dilutata, so it’s quite likely that’s what this one is.

The females have a slightly different wing shape (being a bit broader at the base), and also the hindwings tend to protrude further beyond the forewings when the moth is at rest, so the picture at the bottom left is possibly a female, with the others more likely to be males. The females of the three species can’t be separated even by dissection, so if you really want to know which species a female is the only way is to let the female lay some eggs (which they do readily), breed the caterpillars through and wait for them to emerge the following November. If you’re lucky some of them will be males and then they can be identified to species.

I’ve seen this moth every year since I started trapping, but never more than eight in a single year. And before now, never more than three on the same night, so the five I had on 13th November is a record.

The species name dilutata was assigned to this moth in 1775. It’s from the Latin dilutatus, ‘washed away’ or ‘diluted’, and reflects the fact that the patterning on the wings can appear very faded, even in a fresh specimen.

The Scarce Umber, Agriopis aurantiaria

Year total to date: 1 (13th November)

Although it has ‘Scarce’ in its common name, this species is described as ‘common’ in most reference books. However, this is only the second time I’ve seen this moth (first time was in 2017) so in my book its name is fully justified.

The flight season is November and early December, and like some other moths with flight seasons late in the year it is only the males which are winged; the females have rudimentary wings and remain on the foodplant, for which several deciduous trees including Silver Birch are used. The females climb up the trunks at night to lay their eggs in niches in the bark, or on twigs, and the eggs don’t hatch until new leaves emerge in the spring. This is what the female looks like:

Only a few moth species have evolved to have a winter flight season … whilst this has some advantages, for example the skies are less crowded and the bats are all hibernating, there are disadvantages too. It takes more energy to fly in the cold, nights are often wet and windy and the foodplants will have lost their leaves. This might be why a bigger proportion of these species have flightless females than is the case for species which fly at other times of year.

Having a flightless female involves other trade-offs too. In a previous edition (here) I wrote about the Vapourer moth, whose females are also flightless but where the caterpillars can travel by ‘ballooning’; by spinning silken threads and letting the wind take them, like spiderlings do. But Scarce Umber caterpillars haven’t learnt this trick, and so the only means of dispersal the species has is by the females (and/or the caterpillars) crawling from one tree to the next. This obviously limits the species’ ability to spread and colonise new habitats. Nonetheless, it has still achieved quite a widespread distribution in Britain and Ireland, although according to the Atlas of Britain and Ireland’s Larger Moths it’s abundance at monitored sites has undergone a major decline. This book also comments that the moth’s flight season is now about three weeks later than it was back in the 1970s; this is possibly a response to the warming climate.

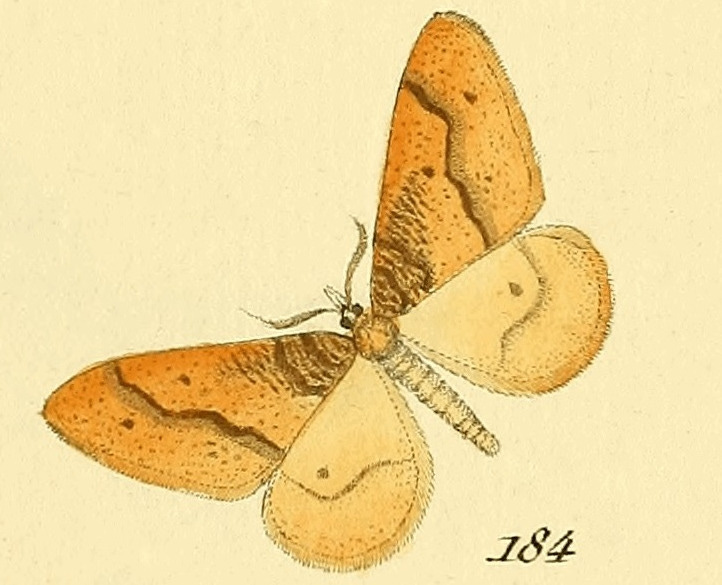

The species name aurantiaria was given to this moth by Jacob Hübner in 1799, it’s from the Latin aurantium which was used for both the colour orange and the fruit; it’s the same root as for aranciata, Italian for orange squash. This is a scan of Hübner’s drawing of the moth (link here):

That’s it for this week. The next issue is scheduled for Tuesday, 2nd December.

We used to call caterpillars that moved along in that humpy sort of way ‘inchworms’. Anyone else?

Band names - Saxon already taken (and I bet they didn’t name themselves after the moth) but Blood-vein, The Feline or Sorcerer might work for a metal band, along with finger in the ear folk outfits, Argent and Sable and Cumberland Gem.