Welcome to my new subscribers (indeed, to all my subscribers!). This introductory blurb (in italics) will remain much the same from post to post; please skip it if you’ve read previous posts.

This newsletter will remain free, I’ve no intention of converting it to a paid subscription. It’s aimed at readers who have a general interest in nature and natural history, but maybe don’t know very much about moths. It’s not really aimed at people who regularly run their own moth traps, but of course they’re welcome to read it (even to criticise it if they wish!).

I run a light trap in my garden in Eastbourne (Sussex, UK) and the main objective of this newsletter is to post photos of some of the moths (and occasionally, other insects) that are attracted to the light, and to say a little about them. On average I run the trap about one night in three, and the plan is to write a post once a week, featuring two or three of the moths seen in the trap within the previous couple of weeks.

In the morning I photograph any catches of special interest, then all moths and other insects caught in the trap are released (if they haven’t escaped already!).

This is my ninth year of running a garden moth trap, firstly three years in Eastbourne (2017-2019), then three in Hurstpierpoint (2020-2022), and then back in Eastbourne (2023 onwards). Hopefully, yet more house moves are off the cards for the foreseeable future!

Report for w/b 24th November

Just one outing for the trap this week, on the Thursday (27th). This was the mildest night of the week , with a forecast minimum temperature around 11 degrees Celsius, but it was also wet and, except for the final few hours of darkness, quite windy. So I wasn’t that surprised to find only two moths in the trap on the Friday morning; another Rusty-dot Pearl (about the latest date I’ve ever seen this moth) and an Acleris sparsana. Then on the following night, although I didn’t put the trap out there was one moth that came to the patio door - Palpita vitrealis.

Thanks largely to the astonishing number of moths around on the 13th, the total number of moths seen for November was an all-time record of 134, the highest count prior to this being from 2020 with a count of 72. The total number of species seen during the month was 30, which is actually the same as for November last year!

It’s interesting to note that I’ve not yet seen a December moth this year; the first year this has happened since 2017. On average I see marginally more of them during November than during December.

Let’s move on to this week’s selection of recently seen species.

The Beautiful Plume, Amblyptilia acanthadactyla

Year total to date: 1 (13th November)

I was beginning to think that I wasn’t going to see this moth this year; I’ve never had a year where I’ve missed it completely but I usually see it in either March/April and then again from July onwards. It has two generations a year, the first in July and the second in September; this second generation overwinters as an adult and the March/April sightings are moths which have emerged from hibernation. So I was pleased when this one turned up on an unusually mild night in the middle of November, before it went into its winter sleep.

James Lowen in Much Ado About Mothing has a rather apt descriptive passage about plume moths:

I became bewildered by the utterly unmoth-like appearance of plume moths. With legs held in an ‘X’ and slender bodies from which feathery wings stuck out at right angles, these twiggy creatures fluttered feebly as a gnat.

The Plume moths belong to the family Pterophoridae; the name is derived from the Greek pteron (πτερόν), ‘wing’ and phoros (φόρος), ‘bearer’ or ‘carrier’. So the name just means ‘having wings’, which could apply to (almost) any moth. However, when looked at closely these moths appear to have more than the usual four wings, because each wing is split into lobes (‘plumes’); two for each of the forewings and three for each of the hindwings. These divisions are not so easy to see when the moth sits in its usual T-shaped resting position; the hindwings in particular are crunched up and hidden beneath the forewings, so the moth appears to have a very small wing surface area to fly with.

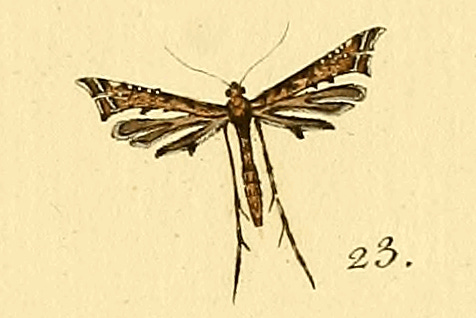

The lobes are more evident in Jacob Hübner’s 1813 drawing of the moth:

Looking at the drawing, you can see a small tuft of dark scales, pointing downwards, about halfway along the lower edge of the lower lobe of the hindwing. This tuft of scales is usually visible when the moth is at rest, as it protrudes below the forewing. It’s not so evident in the photo above (although it can be seen on the right-hand wing), but is more visible in the photo below, coming about a third of the way along the wing; the other tuft at two-thirds is on the forewing.

These tufts are not present in most moths in this family. Unfortunately though, they are also present in the one which is most likely to be confused with the Beautiful Plume; the Brindled Plume (A. punctidactyla). These two species are so similar that it’s possible that I have seen them both but recorded them all as the Beautiful Plume!

This species has demonstrated long-term trends in abundance that are quite unusual. According to Colin Pratt’s A Revised History of the Butterflies and Moths of Sussex, the species was recorded as ‘common and generally distributed’ by Victorian collectors. However, there are few records from the early part of the 20th century and from about 1930 onwards the species disappeared completely from Sussex records, and did not re-appear until the 1990s. Then by about 2010 the species had become common again in most parts of Sussex. The reason for these fluctuations is not known, because the moth’s foodplants, which include garden geranium, have remained common and widely distributed.

The species name acanthadactyla is based on the Greek words akantha (‘spine’) and dactylos (‘finger’), so it translates as ‘spine-fingered’ and it’s possible the ‘spine’ part relates to the tufts of scales I mentioned earlier. Many of the species names for moths in this family end in ‘-dactyla’, referring to the way the wings are dividided into lobes.

The Setaceous Hebrew Character, Xestia c-nigrum

Year total to date: 127 (latest 13th November)

This is a common moth in most of the UK. In the south it has two generations each year, the first flying in May/June and the second, usually present in much larger numbers, in August/September. This one I had on 13th November is the latest record I have for it; I’ve never had one in November before. This year (as is often the case) I saw hardly any of the first generation, but the count of 108 I recorded for August is the highest total I’ve had for that month.

The ‘Hebrew character’ in the common name refers to the black C-shaped mark alongside the pale triangular mark on the forewing. Whether the early entomologists who coined this name had a particular letter of the Hebrew alphabet in mind is not clear; it’s quite possible that it was just that the mark reminded them of Hebrew script in general. But the character it is most commonly linked with is the 14th character of the Hebrew alphabet ‘nun’, which in some fonts appears as ‘נ’. It’s this black mark that also gives rise to the scientific species name, c-nigrum, which is from the Latin and translates as ‘black C’. This name was given to the species by Linnaeus in 1758, so it was among the first group of moths ever to be given a scientific name.

If you’re wondering about the ‘setaceous’ part of the common name, this means ‘bristly’ and is used to separate this species from another common moth, in the same family but not particularly closely related, known simply as the Hebrew Character (Orthosia gothica). This other moth flies in the spring and the flight seasons of the two species do not overlap. I remember reading once that the ‘setaceous’ part of this moth’s name related specifically to bristles (more usually called spurs) on the legs. I haven’t been able to find that reference again, so I checked the legs of both species on the website https://britishlepidoptera.weebly.com - apart from the Setaceous one having slightly longer leg spurs, especially on the hind leg (the longer one), I can’t see much difference!

Fresh specimens of the Setaceous version do show a hairy crest on the thorax, and that could be what this adjective is referring to. It would show up better in a side view, but I don’t seem to have taken any of those. Not that it really matters, because the species are easily separated by their wing patterns and flight seasons.

Another suggestion for the rationale of using the epithet ‘setaceous’ is given by Peter Marren in his book about moth and butterfly names:

‘Setaceous’ means ‘bearing a bristle’, and refers to the white line around the ‘character’ mark.

However I don’t see any sign of such a white line in my photos (although one is clearly present in the Hebrew Character; I guess he must have just got the two species confused). Nonetheless I must thank Peter for pointing me towards another story; that ‘Setaceous Hebrew Character’ was used as a nickname for the 20th century lepidopterist Baron Charles de Worms (1903-1979). He writes:

A well-known Jewish moth collector, the Baron de Worms, whose thinning hair stood up in stiff tufts, was affectionately known by his fellow moth-hunters by that name.

Matthew Oates, in his book In Pursuit of Butterflies: A Fifty-Year Affair also cites this story. He writes that the Baron was accorded this nickname …

…on account of his Austrian-Jewish ancestry and him being distinctly hairy and notably eccentric.

I was a bit puzzled reading these accounts about how one might actually use these three words as a nickname, unless it was as what I think is known as a ‘backstage nickname’, used behind his back. But then I came across an article which I think explains it:

De Worms was a warm-hearted and hospitable man. Entomological friends always looked forward to his Christmas parties, where prizes for games were generally unusual or rare entomological specimens. His friend Russell Bretherton described him as ‘a kindly man, good with cats, dogs and small children. In short, a “character” ’. His friends affectionately referred to him as ‘c-nigrum’, a punning reference to the English name of this moth.

From Michael A. Salmon and others, The Aurelian Legacy: British Butterflies and Their Collectors, University of California Press, 2000, p. 226.

So it looks like it was the Latin rather than the English form of the moth’s name that formed the nickname; this seems much more likely. The photo of him below does not indicate any marked proclivity toward hirsuteness, but that might have worn off by the time this photo was taken!

De Worms also had another nickname, ‘Haemo’. This stems from his professional life working in cancer research, first at the Royal Cancer Hospital and later at Porton Down Experimental Station. I assume from the nickname that his primary interest was cancer of the blood.

One of de Worm’s entomological legacies is the word ‘Charlesing’. To explain it I need to give a bit of background. When moths arrive in the moth trap they sit around on the egg boxes distributed within it, and most of them are just recorded and released without any additional interference, except perhaps for a quick phone photograph to serve as a record. But if the moth-trapper needs to retain the moth for further investigation, or to take a better photograph, it is usually necessary to coax the moth into a ‘pot’. Most people use glass or plastic tubes with stoppers for this purpose, so it’s usually a two-handed operation, one to hold the tube and the other the stopper1. Occasionally (and regrettably) the process goes wrong and the moth gets caught between the two and injured. It is said that as de Worms got older his eyesight started to fail, and the frequency with which this happened to him increased, so much so that injuring a moth in this way became named after him; ‘Charlesing’.

The Baron was a member of the South London Entomological and Natural History Society and regularly attended their meetings for some 50 years. This period covers the (much shorter) period when I was a member myself and attended some of their meetings, so I quite likely met him or at least saw him there. Indeed I remember being told by one of the senior members there that they were engaged in an entomological survey under conditions of great secrecy … but then he couldn’t resist telling me it was a survey of Buckingham Palace Gardens. In an obituary of de Worms’ that is now online it is mentioned that he took part in this survey, so it could have been him. Sadly though, I never got invited to one of his Christmas parties!

If you’re wondering about the ‘Baron’ part of de Worms’ name, it was passed down to him from a great-grandfather who had been made an hereditary baron of the Austrian Empire by Franz Joseph I of Austria in 1871. Permission to use it in Britain was granted in recognition of the family’s service in the development of tea planting in Sri Lanka (Ceylon, as it was then). Charles de Worms never married and the barony became extinct when he died.

In Europe the Setaceous Hebrew Character feeds on a variety of common herbacious plants including nettle, deadnettle, and rosebay willowherb. However in America (where it is sometimes called the Spotted Cutworm) and in Asia it is regarded as an agricultural pest because it also eats alfalfa, clover, corn, sugar beet and lettuce. There have been attempts to monitor population levels in America using pheromone traps. This has led to the interesting discovery that the chemical makeup of the pheromones which best attract the male moths differs from one geographical region to another!

The Spruce Carpet, Thera britannica

Year total to date: 7 (latest 13th November)

Whilst this species was around at the time the common British moths and butterflies were being named (late 18th century), it wasn’t given its britannica name until 1925. The reason for this is that the species was originally assumed to be the same as a wide-spread European species, Thera variata, also (confusingly) called the Spruce Carpet, until it was realised that they are in fact separate species and the British specimens were renamed and given their britannica name. T. britannica is also quite widely spread in continental Europe, where the two species substantially overlap.

To add to the confusion, this species is also very similar to another common UK moth, the Grey Pine Carpet, Thera obeliscata, especially for some of the colour forms of this moth. I don’t claim to be very good at telling the difference between them! Most of the ones I’ve seen I’ve recorded as Spruce Carpets, but it’s really quite likely that some of them (including the one pictured above) are actually Grey Pine Carpets. Both species have two generations a year and fly at much the same times. They do feed on different trees (as their names indicate), so if you see one in a Spruce plantation you could be reasonably confident it’s a Spruce Carpet!

With male moths, there is one difference which can help; that is with the antennae. The male Grey Pine Carpet has ‘threadlike’ antennae, whereas for the male Spruce carpets the antennae are slightly toothed. I don’t see any signs of toothing on the one in the photo above, but of course it might be a female.

I know that a few of my subscribers are experienced moth trappers themselves. If you’re one of these, you’re very welcome to add your opinions in the comments!

That’s it for this week. The next issue is scheduled for Tuesday, 9th December

I don’t use this method. My pots are clear plastic in a cuboid (rectangular prism) shape, with sliding lids which are flush with the edge of the box. To lift a moth off a flat surface is a one-handed operation; I just place the open pot over the moth and slide the lid closed underneath the moth. Accidents are very rare.

Fascinating story of the Baron! May I offer another explanation for the Hebrew character. If it were the letter nun, it would make more sense to just call it C-shaped as English already has a similar letter. To my eyes, if you look at the whole moth (i.e. both sides together), the best match is the aleph (א) which we don't have anything similar to in English, and so would make more sense. But I do prefer the Baron idea! (Although I've always thought it weird when people refer to Jews as Hebrews as it's not particularly accurate!)

‘Charlesing’ - I’ve done it; now I know what to call it!