Moth Report #31

Udea ferrugalis (aka the Rusty-dot Pearl), moth illustrations in books and the Small Marbled

Welcome to my new subscribers (indeed, to all my subscribers!). This introductory blurb (in italics) will remain much the same from post to post; please skip it if you’ve read previous posts.

This newsletter will remain free, I’ve no intention of converting it to a paid subscription. It’s aimed at readers who have a general interest in nature and natural history, but maybe don’t know very much about moths. It’s not really aimed at people who regularly run their own moth traps, but of course they’re welcome to read it (even to criticise it if they wish!).

I run a light trap in my garden in Eastbourne (Sussex, UK) and the main objective of this newsletter is to post photos of some of the moths (and occasionally, other insects) that are attracted to the light, and to say a little about them. On average I run the trap about one night in three, and the plan is to write a post once a week, featuring two or three of the moths seen in the trap within the previous couple of weeks.

In the morning I photograph any catches of special interest, then all moths and other insects caught in the trap are released (if they haven’t escaped already!).

This is my ninth year of running a garden moth trap, firstly three years in Eastbourne (2017-2019), then three in Hurstpierpoint (2020-2022), and then back in Eastbourne (2023 onwards). Hopefully, yet more house moves are off the cards for the foreseeable future!

Report for w/b 27th October

The final trap for October was on the Tuesday, 28th. Although the temperatures were mild, it was quite breezy (and the forecast stays that way for several nights). The total numbers were disappointing (14 moths of 8 species), but one moth in particular made up for it. The only problem is, it’s very small and it’s a tricky one to identify! It’s either Caloptilia hemidactylella or it’s C. honoratella. It’s what you might call an ‘in-betweener’. Both these moths are very rare for Sussex, and I’ve not seen either of them before. I’ll probably just record it as an ‘agg’ (or aggregate).

Also, this moth has the distinction of being my 400th species for the year, which is my highest ever annual total, and hopefully will go up by another half dozen or so species by the end of the year. It also brings the species count for October to 64, another record, my highest previous count being 59. I said at the beginning of the month (here) that maybe the good weather this summer had just moved everything forward a bit, in which case this would be reflected in a dearth of species at the end of the year. This does not seem to have happened, suggesting that this has been a good year for moth diversity all round.

Anyway, let’s move on to look at some species seen recently.

Udea ferrugalis (aka the Rusty-dot Pearl)

Year total to date: 36 (latest 28th October (5))

The species name for this moth, ferrugalis, is from the Latin ferrugo, ‘rust’. It’s one of the micro-moths that has a well-established English common name, the Rusty-dot Pearl, also based on the same idea; it’s easy to see how the name originated from the rust-coloured marking on the wings. Actually, although I described the English name as well-established, one of the older books (published 1952) I have on this family of moths actually calls it just the ‘Rusty Dot’; the ‘Pearl’ bit was added later and was applied to several closely-related species. The whitish legs are are a feature of several of this same group of species.

This moth is most usually seen in this country as a migrant from the continent, and although it can breed here during the summer it is not believed to be able to survive our winters (yet!). As a migrant it displays two of the classical signs; firstly it is most commonly seen near the coast (although it has been found throughout the British Isles (although not so frequently in northern Scotland), and secondly it is much more abundant in some years than others.

My own records demonstrate this latter feature; since I started trapping in 2017 the lowest annual count was just two in 2018, but in 2023 I had 32 and so far this year, 36. But seems I just missed out on one of the bonanza years, which was 2016; at a light trap in Peacehaven (also on the south coast, about 14 miles west of Eastbourne) a total of 792 were recorded in that year. As well as varying between years, numbers can vary wildly within years as the migrant moths arrive in waves when the wind is in a favourable direction. Of the 32 moths I saw in 2023, 16 arrived on the same October night.

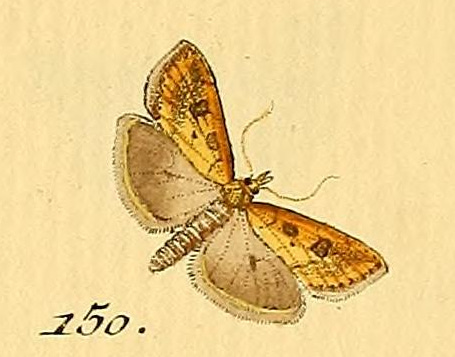

The name ferrugalis was given to this moth in 1796 by the German entomologist Jacob Hübner (1761-1826), whom I mentioned briefly in an earlier post (here). Hübner trained as a designer and engraver, and for three years from 1786 he worked in this capacity in a cotton factory in Ukraine. While there, his fascination with butterflies and moths increased, eventually becoming his dominant interest. He named hundreds of species and many genera, and many of these names are still in use today. His meticulous illustrations and species descriptions formed a cornerstone of entomological literature. This is his illustration of the Rusty-dot Pearl, taken from his book Sammlung europäischer Schmetterlinge (‘Collection of European Butterflies’), published in parts between 1796 and 1805:

(Link to the scan from which this picture is taken here).

The diversion which follows is somewhat longer than my usual diversions, so I’ve given it its own section.

Moth illustrations in books

I’ve mentioned in a couple of previous Moth Reports how the style in which illustrations of moths in text books has changed over time, but my previous comments might have been a bit misleading in some respects. Let’s look at a modern field guide then work backwards.

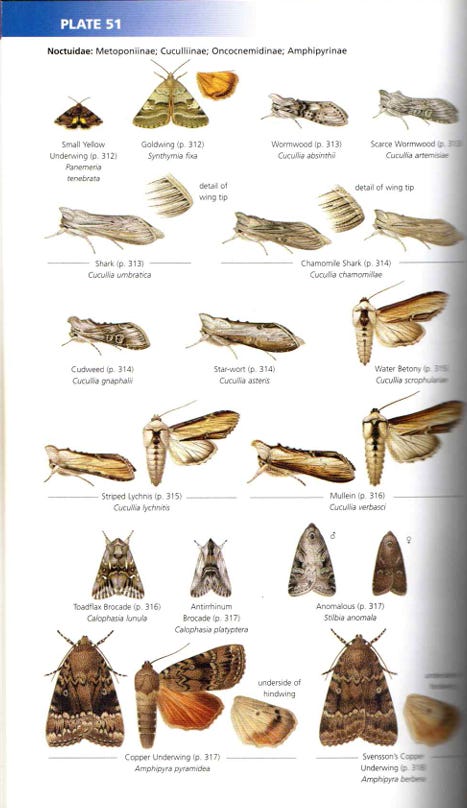

This is a plate from Field Guide to the Moths of Great Britain and Ireland (Third edition) by Waring and Townsend, published in 2017. The illustrations are by the talented artist Richard Lewington. The typical illustration shows the moth in its normnal resting position, either from above or from the side. Individual wings are shown extended (i.e. in the ‘set’ position) only if they show features which are critical for identification.

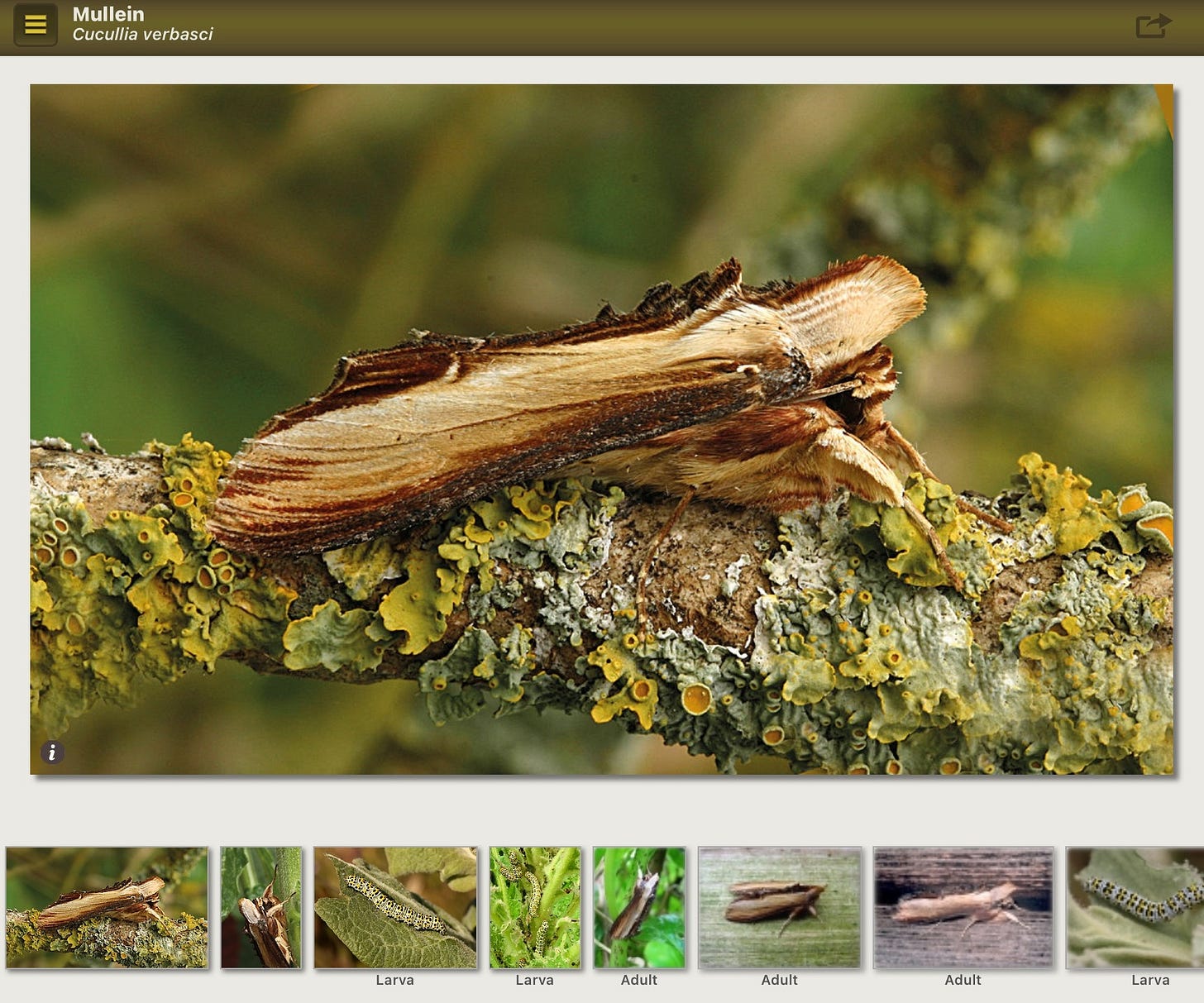

Some books dispense with hand-drawn illustration altogether, for example British Moths: A Photographic Guide to the Moths of Britain and Ireland by Chris Manley uses only photographs of live moths. The second edition is dated 2015. I don’t actually possess a printed copy of this book, but I have an electronic version which I find very useful. Most species show several photos; here is an example from my iPad:

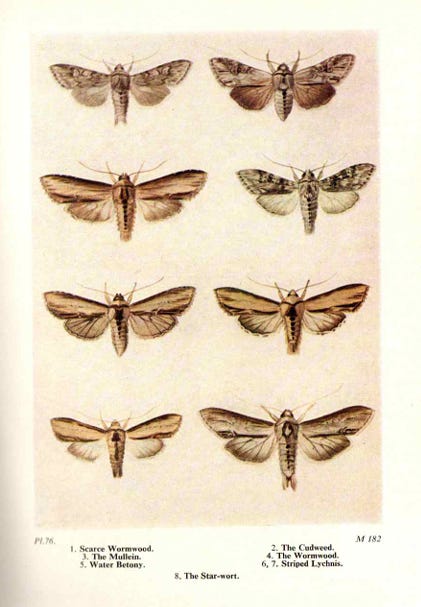

The plate shown below is from Moths of the British Isles by Richard South. The edition I have was published in 1961, but the first edition dates from 1907. The illustrations all show the moths in their ‘set’ position, and all aligned with their heads pointing to the top of the page. According to Copilot, illustrations for the first edition were based on photographs of museum or collectors’ specimens, reproduced using chromolithography. However the 1961 revised edition used colour photography for printing the plates.

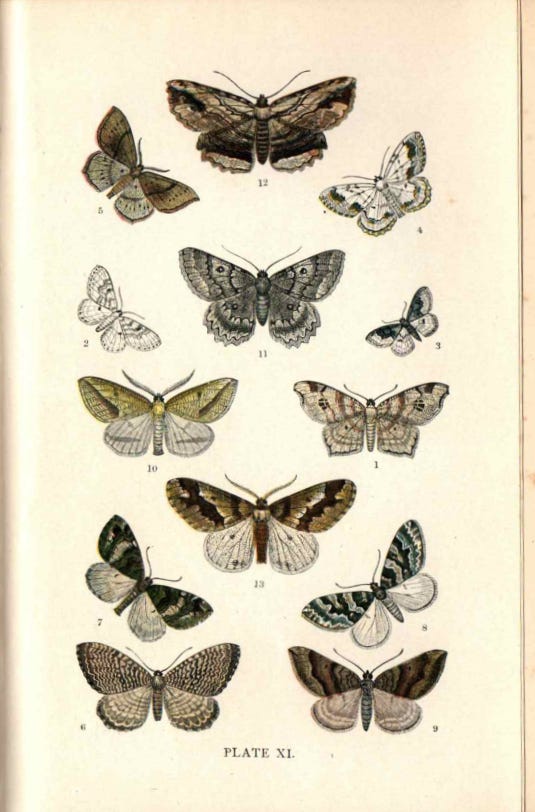

I don’t have any of the earlier editions of South’s book. I suspect that the change from chromolithography to colour photography was made on the basis of cost. However, I do have an original copy of an earlier book, J.W. Tutt’s British Moths, published in 1902. This book has only twelve colour plates, but they were printed by chromolithography. Here is Plate 11:

The quality of these plates actually looks better to me than the plates in the 1961 edition of South. Also, although some of the moths in the plate are shown with their heads pointing directly north, others are shown at an angle, perhaps to make a more pleasing visual layout.

Going back to the early days of moth/butterfly books, we find none of the moths are shown with their heads pointing straight up; they are all positioned at an angle and some are even shown in a position we would today consider to be almost upside-down:

This is a plate from Beiträge zur Geschichte der Schmetterlinge by Hübner, published in parts between 1786 and 1790. These books were published with ‘hand-coloured’ illustrations; the printed books would contain just faint outline drawings, and each individual copy of the book was completed by a skilled colourist (they often worked in teams) using watercolour or gouache to complete each plate. This book contains 48 plates, so that’s quite a lot of work, just for one copy of the book!

Before leaving the topic of preparing plates for books, perhaps I can throw in a story of my own. In 1970 I was staying with my friend and colleague Denis Owen (Wikipedia entry here) at his campus bungalow in Fourah Bay College (now the University of Sierra Leone), Freetown. Denis was in the process of writing a book, Tropical Butterflies (here), in which he wanted to include a colour plate illustrating one of the mimetic complexes he had discovered in the nearby forest. The task of taking the necessary photograph was delegated to his wife, Susan (as were most tasks of a technical nature!). This was something Susan had never done before, and there was quite a bit of discussion about how to achieve it. The main problem was how to light the butterflies in such a way that they didn’t leave shadows.

Susan’s research suggested that the way to do this was to arrange the butterflies on a ground glass plate, with blobs of plasticine to hold the pins firm, and shine additional lights onto a white surface a few inches below the plate in order to eliminate the shadows. This is a photo I took using the setup she assembled:

As you can see it’s not 100% successful, but actually not far off. In the published book, the printers have managed to remove what’s left of the shadows. The butterflies also all have full pairs of antennae (I think those missing in my photo above got lost in the process of scanning the photo from a 35mm colour slide, the software probably thought they were noise!).

For anyone interested in what the butterflies in this plate are, those in the left column are all different species of Bematistes, distasteful species in the family Acraeidae (the models in the mimetic assemblage). The mimics in the right column are all colour forms of the same species, Pseudacraea eurytus, a palatable butterfly in the Nymphalidae family. So this is an example of Batesian mimicry. I won’t go into any more detail here, since it’s not the main subject of this post, but I wrote a bit about mimicry (and Henry Bates) in an earlier edition of this newsletter (here).

The Small Marbled, Eublemma parva

Year total to date: 1 (21st October)

The scientific species name for this moth, parva, means ‘the little one’, and is very apt for this species which has a wing length of just 8mm. Nonetheless it is actually a macro-moth, belonging to the same family, the Erebidae, as some much larger species. These include a couple of species I have written about in earlier editions of this newsletter; the Garden Tiger (here) and the Red Underwing (here).

In contrast, the moth with which I began this edition, the Rusty-dot Pearl, is a micro-moth, but it has a wing length of 10mm so it is actually larger than the Small Marbled. I managed to get a photo of them together (well more or less!):

Both these moths are migrants, but while the Rusty-dot Pearl is common in the UK, the Small Marbled is considered a scarce migrant - this is the first one I’ve ever seen. Most sightings are recorded as June or July, although there have been some October records. The Small Marbled is primarily a moth of southern Europe and northern Africa, but UK records have become more common in recent years. By 2019 the total number of UK records was around 600, mainly from the south coast of England (with a bias towards south-western areas), but there are records throughout most of England and few from Scotland.

Like the Rusty-dot Pearl, this moth was also given its species name, parva, by Jacob Hübner. This is his illustration of it:

One of the foodplants of the Small Marbled is Fleabane, although caterpillars are rarely found in the UK. But when I was living in Hurstpierpoint there was a meadow nearby (Hurst Meadow) in which there was quite a lot of Fleabane, and over the three years I did spot a couple of insects which are not particularly common which have associations with that plant. One was a fly, the Fleabane Gall Fly, Myopites apicatum:

The other was a day-flying moth, Tebenna micalis:

That’s it for this week. The next issue is scheduled for Tuesday, 11th November.

Excellent. And good to hear that it’s been a genuinely good year for moths!

400 species! Impressive.