Welcome to my new subscribers (indeed, to all my subscribers!).

This newsletter will remain free, I’ve no intention of converting it to a paid subscription. It’s aimed at readers who have a general interest in nature and natural history, but maybe don’t know very much about moths. It’s not really aimed at people who regularly run their own moth traps, but of course they’re welcome to read it (even to criticise it if they wish!).

I run a light trap in my garden in Eastbourne (Sussex, UK) and the main objective of this newsletter is to post photos of some of the moths (and occasionally, other insects) that are attracted to the light, and to say a little about them. On average I run the trap about one night in three, and the plan is to write a post once a week featuring two or three of the moths seen in the trap within the previous few weeks.

In the morning I photograph any catches of special interest, then all moths and other insects caught in the trap are released (if they haven’t escaped already!).

This is my ninth year of running a garden moth trap, firstly three years in Eastbourne (2017-2019), then three in Hurstpierpoint (2020-2022), and then back in Eastbourne (2023 onwards). Hopefully, yet more house moves are off the cards for the foreseeable future!

Report for w/b 1st December

I ran two trapping sessions this week; the 2nd (Tuesday) and the 6th (Saturday). Both nights were mild, but rather windier than I would have liked. Nevertheless the first session produced two moths, one male and one female December moth, pretty much right on cue! I’ll discuss this species in next week’s report. But Saturday’s session was blank; I’m hoping a Winter Moth will put in an appearance soon, but they’re not strong fliers and are more likely to appear when there’s less wind.

With this report my newsletter reaches something of a milestone - the first moth described below (The Sprawler) is the 100th species to have been featured in my reports! When I first started writing the newsletter in mid-June I wasn’t sure how well it would work and how long I would be able to keep it going, but complimentary comments and the steadily growing number of subscribers have been very encouraging. Consequently I hope to be able to keep it going for at least the next 100 species.

In recognition of this milestone, and following Chantal Bourgonje’s example in her excellent newsletter Flowerology, I shall shortly be issuing an index which should enable you to go back to the relevant report if you’re interested in a specific moth (or person). I shall attempt to keep the online version of the index updated. I shall also transfer the introductory blurb with which I begin each report into the index, and drop it from ongoing reports, just giving a link to it in each future report. If you get my newsletter by email the index should be in your inbox in a couple of days; it will be additional to the usual weekly report.

Having said the usual report comes out weekly, you will probably be aware that the number of moths that are around falls off quite dramatically during the winter; last winter for example I had only one moth during the whole of January and February (although usually I get a few more than that). So I will need to make some changes for the winter, which will probably include reducing the frequency, perhaps to fortnightly, until the numbers begin to increase again.

Anyway, let’s move on to look at a couple species seen recently; just two this week as there aren’t so many about!

The Sprawler, Asteroscopus sphinx

Year total to date: 1 (23rd November)

In the nine years’ trapping on which these reports are based, this is only the sixth time I’ve seen this moth. All sightings were in November or December, although according to the books the flight season actually begins in October.

The species part of the scientific name is interesting: sphinx. It was bestowed on this species by Johann Hufnagel in 1766. One theory is that this is a nod to the hawk moths, often called sphinx moths in the US, and indeed it’s the genus name of the Privet Hawk moth, Sphinx ligustri. Now Sphinx is the oldest moth genus in existence; it was coined by Linneaus in 1758 … in his publication Systema Naturae he named only three genera for the whole of the Lepidoptera; Papilio for all the butterflies, Sphinx for all the hawk moths and Phalaena for the rest of the moths. So it is perfectly feasible, indeed likely, that Hufnagel knew about the genus Sphinx. But why would he choose it as a species name for this moth we now call the Sprawler - it doesn’t look like a hawk moth at all?

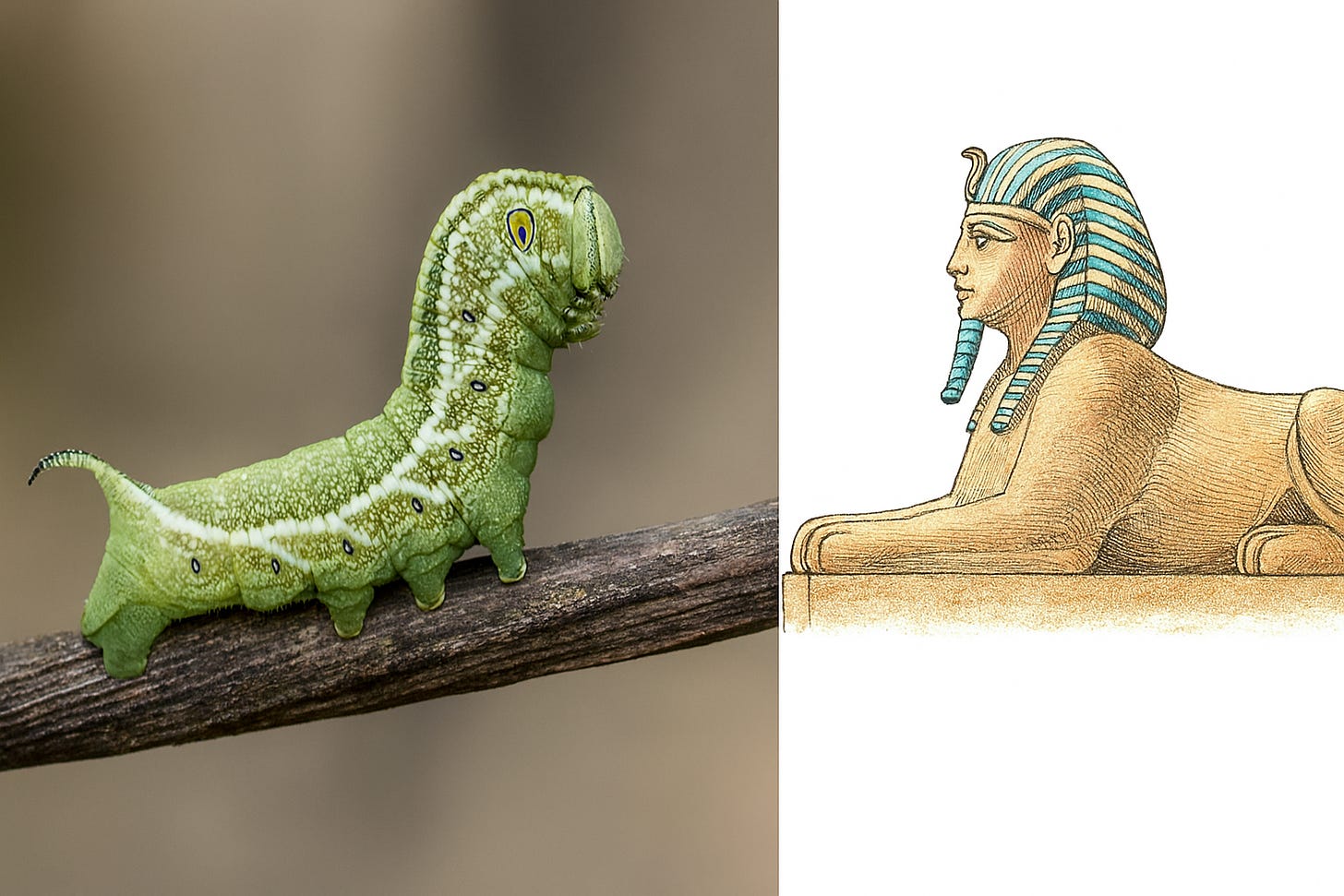

To answer this, I think we should first look at why Linnaeus chose the name for his hawk moth genus. It would appear to be based on the appearance of the caterpillars, which when alarmed adopt a defensive posture in which the front end is raised and then held still, like a statue. Here is a Copilot-generated image which compares the typical hawk moth caterpillar’s defensive pose with the Great Sphinx of Giza:

Well the likeness might not be that great, but we should remember that Linnaeus hadn’t seen the real Sphinx, he would only have seen drawings or paintings of it!

So then we come back to the Sprawler. It turns out that the caterpillar has a similar defensive posture when alarmed; it raises its front section, as seen in this photo:

This I think looks even less like the Sphinx, but I guess it’s probably the similarity in behaviour between this caterpillar and hawk moth caterpillars that suggested the species name sphinx to Hufnagel. Another way of viewing the caterpillar’s pose is that it’s looking upwards, towards the stars. Hence the genus name, Asteroscopus; literally a star-scope.

Apparently this larval behaviour is also what gave rise to the moth’s common name, the Sprawler; so in fact all three components of its name relate to the behaviour of the caterpillar.

While we’ve touched on the defensive poses adopted by some caterpillars, I can’t resist showing you this picture of the caterpillar of a south/central American hawk moth, Hemeroplanes triptolemus. It knocks the Sprawler’s attempt into the proverbial cocked hat!

(If you follow the link in the caption, there are more photos of this astonishing caterpillar on Flickr).

Acleris sparsana

Year total to date: 5 (latest 27th November)

Back in July I wrote a bit about another member of this genus, Acleris forsskaleana (here). In that edition I wrote:

I think it’s a beautifully marked moth; indeed, several of the species in the (rather large) genus Acleris are really quite stunning, abeit on a small scale. None of them is common, but hopefully I’ll be able to show you some more of them in due course.

Although over the years I’ve recorded 11 different species of this genus, this year I’ve seen only these two. That’s doubly disappointing, firstly because in every previous year when I’ve been trapping I’ve always seen at least three of them, sometimes five or even six, and secondly because, having promised you a feast for sore eyes this second species I’ve seen this year, A. sparsana, is probably the least stunning of them all … the species name sparsana rather hits the nail on the head!

The moth’s main flight season is October and November, with intermittent sightings on mild nights at least until January. So it gives the appearance of trying to hibernate, but there’s no spring re-appearance of the moth, and it seems the adults can’t survive until the spring. In Sussex there is a small peak in appearance in July, but the numbers then decrease until the main flight season starts in October.

The name sparsana is attributed to ‘Denis & Schiffermüller, 1775’. Previously in these reports I’ve talked about several species where the same attribution (and date) is given, but without saying anything about these authors. The reason for this is that the story is a bit complicated! However, it’s probably now time to make an attempt at filling the gap.

Denis & Schiffermüller

The best place to start the story is probably in Vienna in 1746 when Empress Maria Theresa sold her summer palace to the Jesuits, in order for them to transform it into an educational institution to train young men for the civil service. The palace was renamed the Theresianum, and the ‘imperial academy’ was instructed to operate to the highest pedagogic and scientific standards.

In 1759 a new teacher of architectural drawing joined the staff of the Theresianum, one Jeremias “Johann” Ignaz Schiffermüller (1727-1806). This new teacher was interested in butterflies and moths, and took part in one of the scientific projects the Theresianum had instigated; a study of the fauna local to Vienna. This project concentrated on butterflies and moths, and at least five of the Jesuit teaching staff of the Theresianum took an active part in the project. Most of the moth species were collected as caterpillars and bred through to adults.

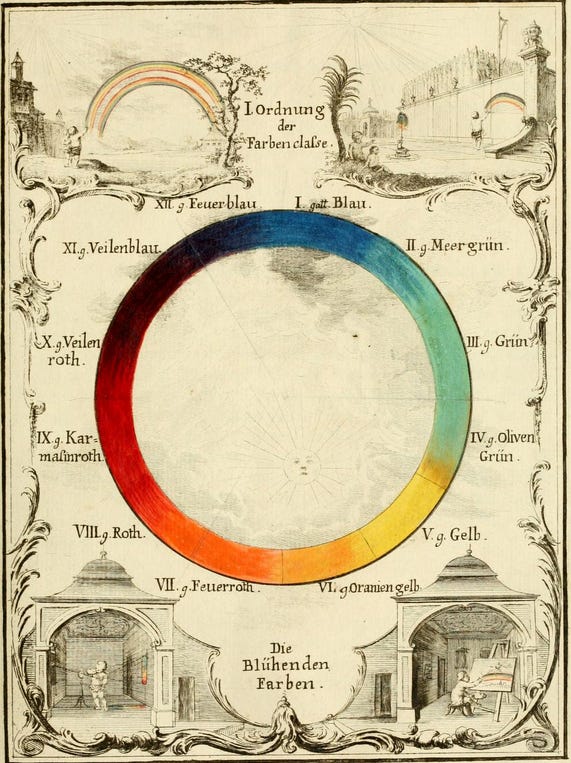

Schiffermüller himself was particularly interested in developing a system to describe the colours of nature (and butterflies in particular) in a standardised way. In 1771/2 he published a book Versuch eines Farbensystems (‘Treatise on a Colour System’), which included this colour wheel:

This was one of the first publications on colour to place complementary colours opposite one another.

But during this time the Catholic monarchies of Europe were becoming increasingly concerned about the influence of the Jesuits, accusing them of political intrigue, possession of too much economic power, and resistance to royal authority. In 1773 Pope Clement XIV yielded to pressure from these monarchs and issued a papal decree formally suppressing the Jesuit order worldwide. The Theresianum staff were disbanded and the college was closed.

It’s not altogether clear what happened to the work done by the project team that had been studying the local Lepidoptera. On the first page of Schiffermüller’s 1771/2 book there is a reference to another work, Ankündung eines systematischen Werkes von den Schmetterlingen der Wienergegend (‘Announcement of a Systematic Work on the Butterflies and Moths of the Viennese Region’) which can be read as indicating that this work was already published, or at least in the final stages of preparation. However, no such work appeared in 1771 or 1772.

There are some clues in contemporary documents that there were plans to add illustrations to the publication; Schiffermüller was a talented artist and this was well within his capabilities. Probably what happened is that the text was completed but the publication was held up waiting for the illustrations to be ready, but was then completely disrupted by the closure of the Theresianum and the dissolution of the Jesuit order. In 1806 an unpublished biography of Schiffermüller, probably written by himself, included the passage:

With regard to copper engravings and illumination, every arrangement had been made — yet once again there came a hostile, all‑destroying fate.

However in 1775 a few copies of the work announced in the Versuch eines Farbensystems did materialise, describing some 1150 species but with minimal illustration, and no author is named. It merely states on the title page ‘Herausgegeben von einigen Lehrern am k. k. Theresianum’ (‘Published by some teachers at the Imperial-Royal Theresianum’). The work is groundbreaking in the way that information about the caterpillars and foodplants is incorporated into the taxonomic organisation of the book.

Over the past 20 years or so several academic papers have been written discussing who the teachers involved in preparing the text were, and what their individual contributions might have been. It seems clear that Schiffermüller was the principal author and the driving force behind the publication, and four other names have been identified as being associated with the work. One of these is Michael Denis (1729–1800), a Jesuit priest, poet and librarian, who was well known in literary circles and who was also interested in natural history. However, there is no evidence that he played a bigger part in the work than any of the other three Jesuits known to be associated with it, other than the observation that Denis was a poet and the text does get quite poetic in places. Quite how the work has come to be described as by ‘Denis & Schiffermüller’ is a bit of a mystery, and it has been proposed that the authorship of the species names introduced in the book should be amended to Schiffermüller only.

In the following year (1776) the work was republished under a different title, in sufficient quantities for Schiffermüller to be able to distribute copies to various naturalists, including Linnaeus. The moth collection on which the book was based was relocated, eventually ending up in the Hofburg Palace, although some of the material was subsequently transferred to the imperial collections and this material now forms part of the Vienna Natural History museum collection. The bulk of the collection though was destroyed in the Hofburg fire of 1848 which occurred during the Vienna uprising.

Schiffermüller had prepared some 400 detailed and accurate illustrations of larvae, pupae and foodplants in readiness for the aborted illustrated edition of the book. These drawings, together with the collection of adults, was made availabe for study by other entomologists including Jacob Hübner whom I mentioned in earlier articles (here). Indeed, Hübner’s illustrations of caterpillars are direct copies of Schiffermüller’s (which are now in the Natural History Museum in London). Direct, that is, apart from a left-to-right inversion; apparently that is quite common when copper engravings are involved. There is a detailed discussion of Denis and Schiffermüller’s work here, including reproductions of some of the caterpillar paintings.

That’s it for this week. The next regular issue is scheduled for Tuesday, 16th December, but there will be another post before then (probably on the 11th) containing the index I wrote about above.

Love these reports. I had my first ever Sprawler a couple of weeks ago. Name did seem strange for a fairly ordinary moth. I love moth trapping for still turning up new species four years in.

Fascinating research! (Re the Sprawler, perhaps you might have given a mention to the ‘claws’ on the front legs, which are so easily visible in this species - eg https://www.flickr.com/photos/149980226@N06/54924114415/in/dateposted-public/