This is the first of a new format report in which the introductory blurb no longer appears, but it can be read using this link to the index which I issued a few days ago. If you’re new to these reports you can find some background there.

Report for w/b 8th December

Although nights have been quite mild recently, mostly they’ve been too windy to be worth putting the moth trap out. But for Thursday night (11th) the forecast wasn’t too bad, so I put the trap out and it produced 18 moths of 7 species. That’s better than for the whole of December for either of the previous two years!

There were no new records for the year, but a couple of species worthy of note were Palpita vitrealis and Udea ferrugalis (Rusty-dot Pearl). These are both autumnal moths which migrate from France, but I’ve never had either of them in December before.

Then on the following night, which was both colder and less windy, I did get a new record for the year when a Winter Moth appeared at the patio doors!

Let’s move on to look at some species seen recently. Again, only two this week owing to the general scarcity of species around at this time of year.

The December Moth, Poecilocampa populi

Year total to date: 5 (latest 11th December (3))

I usually see my first December moth of the year in November, but this year I didn’t see the first one until I had two (a male and a female) on 2nd December. You can see from the photo that the female is larger than the male, and doesn’t have the pale collar that the male has. I haven’t kept records of the sex of the ones I’ve seen, but males are definitely trapped more frequently than females and most of my photos are of males.

In his book Much Ado About Mothing James Lowen describes this moth as

…. hulking, hairy and black. With its buff brow-band, seen front-on, the resemblance to a Musk Ox is uncanny.

See what you think:

Like most other moths in the same family (Lasiocampidae), December Moth adults have only rudimentary mouthparts and do not feed; all the feeding is done by the caterpillars, and the adults survive (but for a few days only) on food reserves built up during that stage. But as a winter-flying moth, feeding at night on nectar-rich flowers would be rather impractical anyway because there aren’t many such flowers in bloom in December! And searching for any which are would use up more energy than it does in spring and summer.

Several other winter-flying moths have flightless females (I already discussed the Scarce Umber (here), and the Mottled Umber is featured below), but the December moth has not evolved down this path. Instead both sexes have a number of adaptations which enable them to survive low temperatures. I once came across a photo of a December moth with several frost crystals on it. I haven’t been able to track down that photo, so you’ll have to make do with one with some raindrops (or maybe dew) on it:

The general hairiness of the December Moth is one of its adaptations against the cold. It’s a strong flier and needs to have warm flight muscles; like many other species the moth can warm up its flight muscles by vibrating them, and the hairiness helps them retain the heat.

Many winter-flying moths have what’s commonly described as ‘antifreeze in their blood’. Their haemolymph (equivalent to our blood) contains glycerol, which reduces the freezing point of their body fluids. Their eyes and antennae also contain specialised proteins that prevent them from freezing so that they are still able to navigate and find mates in very cold weather.

Another technique the December moth is reported to use to tolerate below-zero temperatures is to be able to expel water from its tissues in order to prevent them from being damaged when the water freezes. Having said that, I found this information on only one or two websites about this moth, with no reference to a scientific paper, so I wouldn’t take it as gospel. I did however wonder whether the beads of water in the photo above were the results of such a process, rather than being raindrops or dew. But when I checked my records they confirmed that the photo was taken following a very mild night, so it doesn’t seem likely.

Having said that, the December moth is still a relative amateur at dealing with cold temperatures; Lees and Zilli in their book Moths; Their biology, diversity and evolution report on the High Arctic moth Gynaephora groenlandica which has been recorded as surviving temperatures as low as -70°C. Living in such a cold climate means it can take up to 15 years to complete its life cycle. It has a quite extensive Wikipedia page (here) if you want to read more about it.

The Mottled Umber, Erannis defoliaria

Year total to date: 1 (14th November)

Whilst I see more Mottled Umbers than I do Scarce Umbers (which I wrote about here), I still don’t see large numbers of them. This is another moth that has its adult phase in winter, and where the female is flightless. I’ve seen the males nearly every year, but never more than four in any one year. The caterpillars feed on a wide variety of deciduous trees, including some which I have in my garden, but most likely this moth is most abundant in woodland rather than gardens, and I see only the occasional straggler.

The wing colours in the male are quite variable, and sometimes the pattern is well marked while sometimes the colour is almost completely uniform. Fortunately some moth trappers see larger numbers than I do, which enables them to get pictures like the one below, showing this variety of colours.

As mentioned above, the Mottled Umber is one of those cold-season moths where the female is flightless, like The Scarce Umber I wrote about recently (here). But while the Scarce Umber female does have rudimentary wings, the female Mottled Umber has none at all. And rather than being dark all over, it is off-white with dark spots.

This moth was given its species name, defoliaria, by Carl Clerk in 1759; this is interesting for two reasons. Firstly, the choice of name itself implies that the caterpillars are capable of defoliating their host trees, and at one time this moth was indeed considered an agricultural pest of apple trees and the moth could sometimes be a problem in orchards. But apple is the only foodplant of commercial interest, and for the many other woodland trees available to it any damage just slows the growth of the tree but is unlikely to harm it otherwise. These days it is not considered a major pest of apple production.

The other thing of interest is the date. Carl Alexander Clerk (1709-1765) was Swedish and a contemporary of Linnaeus. He lived in Stockholm and worked in government administration, including in the tax office. He became interested in natural history when he attended a lecture given by Linnaeus in 1739. His main interest was spiders, and in 1757 he published Svenska Spindlar (‘Swedish Spiders’), the first book ever to give binomial scientific names to individual species using the Linnaean system. He actually beat Linnaeus himself to this, since Linnaeus didn’t publish his Systema Naturae until the following year, 1758. Linnaeus’s names for spiders were adopted from those proposed by Clerk, and in the few cases where there are differences Clerk’s name is now accepted as having precedence.

Then in 1759 Clerk published another work, Icones Insectorum Rariorum (in Latin only this time rather than Swedish and Latin as used for the spider book) in which he proposed names for about fifty moth species as well as some butterflies and beetles. It is this book where Clerk proposed the name defoliaria for the Mottled Umber.

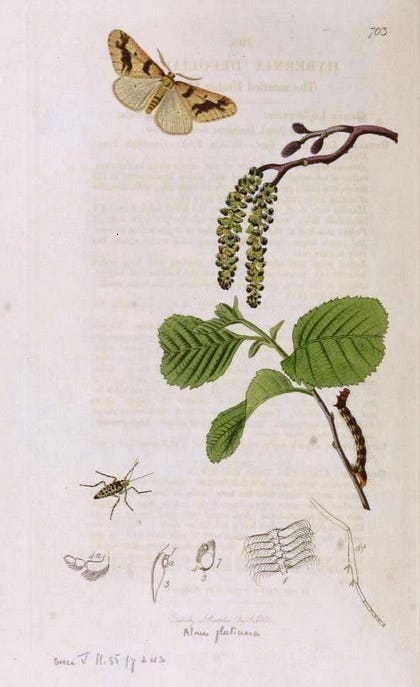

Although Clerk did include an illustration in his 1759 book, I’ve opted to show you instead an illustration made by John Curtis (1791-1862), from his book British Entomology (it actually has a much longer title1 ) which he published in 8 volumes between 1823 and 1840. This illustration is from Volume 6 (1834 or 1835), and shows both sexes, the caterpillar and one of its foodplants (it has many), as well as some detailed diagrams of various parts of its anatomy.

I’ll come back to John Curtis again in a future report, but meanwhile here is a part of his text about this moth from the same publication:

Fortunately in this country the larvae are never known to do any mischief, but in France caterpillars of the species figured sometimes do very extensive injury by destroying the leaves, especially of fruit trees; but M. Duponchel mentions an admirable plan for checking their ravages: it is by washing a space round the base with a glutinous matter, so that the females as they pass up the trunk in order to lay their eggs upon the leaves, may be entangled by the gluten and perish, and he adds that by the destruction of one female the birth of 300 caterpillars at least is prevented. Shaking the trees smartly is also effective by causing the larvae to fall, but it is likewise injurious to the fruit.

That’s it for this week. The next issue is scheduled for Tuesday, 23rd December. This will be a special Christmas Edition! Instead of looking at UK moths, I’ve chosen three moths from warmer climes (one from Africa, one from India and one from Sri Lanka) seen by some of my subscribers over the past six months.

British entomology; being illustrations and descriptions of the genera of insects found in Great Britain and Ireland; containing coloured figures from nature of the most rare and beautiful species, and in many instances of the plants upon which they are found

Last night (Monday 15th December) by 6.45pm there were ten male Winter moths on our patio doors, and three more on other windows.

As a relatively new subscriber to your report I wonder how you identify each month as there seems to be such a varied appearance for each species as I am used to identifying by looks